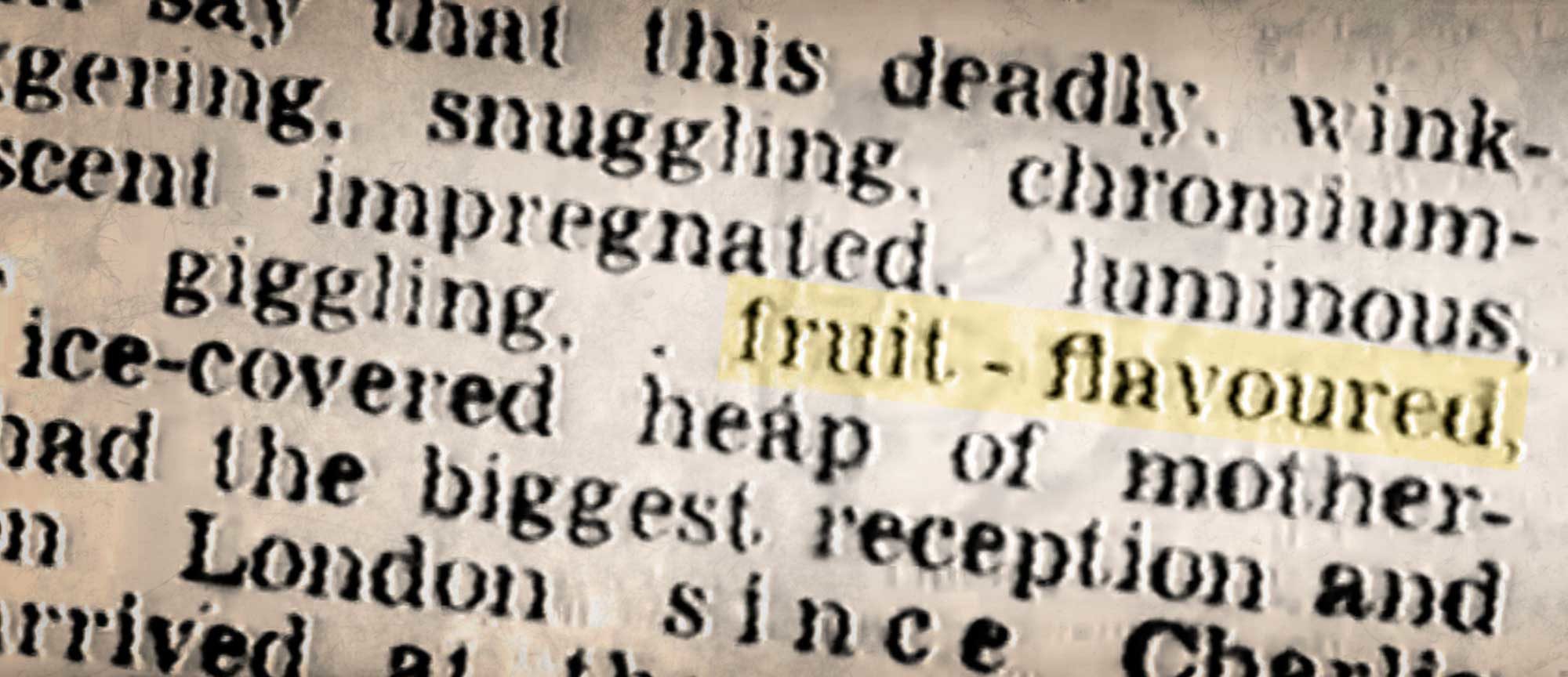

A jury of ten men and two women agreed that Wladziu Valentino Liberace — just Liberace to his fans — was not a deadly, winking, sniggering, snuggling, chromium-plated, scent-impregnated, luminous, quivering, giggling, fruit-flavored, mincing, ice-covered heap of mother love.

That decision came on June 17, 1959, following a week-long libel trial at Queen’s Bench IV in London. Liberace had somehow convinced the jury that Daily Mirror and its columnist, William Connor, had libeled him by suggesting that he, Liberace, was not the man he pretended to be. That he, Liberace — of lilting voice, fluttering fingers, flamboyant costumes and an unusually close attachment to his mother — hadn’t been entirely straight with his fans. That he had misled those fans, most of them women of a certain age and matronly disposition, with his mediocre low-brow musicianship, his sickly-sweet reverence for God and mother, and his fluttering eyelashes and twinkling, winking eyes.

Of course, we know today that Liberace did, in fact, do all of that. But there was no malice involved. It was all done self-protection. Homosexuality was illegal throughout the English-speaking world, and just about everywhere else besides. And even a hint of feyness was career poison. This was true whether that career was in show business or the mail room of a government office.

If someone like Liberace were to make it in show business, he would have had little choice but to do as he had. He presented himself as dedicated family man to his mother and brother, and as a dashing lover on the constant lookout for a beautiful and perfect wife, just like mom. For more than a decade, he had managed to construct the world’s most glittering closet. But with just a few well-chosen words in a small column in a British tabloid, the security locks to his closet were very nearly picked.

Today, t’s hard to understand how Liberace managed to build his fabulous closet. Look at his 1952 syndicated television variety show. It was all there for anyone willing to look. Even in his pre-costumed era, his mannerisms and voice, his campy style, and his mother-fixation — all of this suggested something considerably less than red-blooded masculinity. To modern audiences, The Liberace Show looks more like a big bay window draped in chiffon and velvet instead of a dead-bolted closet door. And yet, that very program actually made his closet possible.

The Liberace Show was filmed before a studio audience, but Liberace understood that his real audience was at home. He broke the first rule of Hollywood by looking directly into the camera, thereby creating a direct, intimate link with women in their living rooms. As his fingers slid across the keyboard, he looked straight into the lens, smiled and winked. That wink, like Cupid’s arrow, shot into living rooms across America and found its target in the hearts of millions of nerdy teenager girls and their mothers. That wink was almost as much his trademark as his ostentatious candelabra.

The other trademark, of course, was his Polish-born mother. If she wasn’t seated in the front row, she was on stage where he could dote on her. And his brother George, Liberace’s bandleader and violinist, was never far away. And for good measure, Liberace often called children up from the audience and played for them.

And so there it all was: his ersatz sophistication, his ability to pronounce Rachmaninov (even as he butchered the Piano Concerto #2 In C Minor down from thirty-four minutes to four), his love of mother, brother and children, his reverence for God and family, his generosity and fun-loving nature, his wavy hair and dimples, his smile and wink. He was perfect in every way. All he needed was a wife.

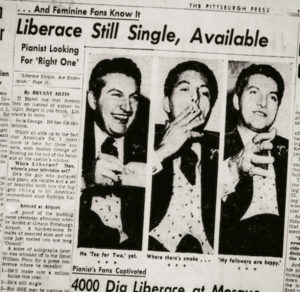

Still Single, Still Available

This is where his over-active publicity team came in. They blanketed newsstands with stories about what he wanted in a wife, who his favorite dates were, and why he hasn’t married yet.

In 1954, Liberace’s people put out a rumor that he was engaged to a young dancer named Joanne Rio. His fans hated the idea. Letters ran four-to-one against it. A sixty-five year old widow wrote, “I feel sorry for your mother. The adoration you give her will have to be shared.” Another woman wrote, “How can you think of marriage? You belong to us.” One warned that Rio was too pretty. “Don’t forget Joe DiMaggio and the promises she (Marylin Monroe) made to him!”

His public had spoken. They didn’t want him to marry. Which suited Liberace just fine. He broke off the engagement. Actually, he claimed they were never engaged in the first place. Besides, he said, “There are too many things I want to do. I want to play in Europe and make movies. My kind of schedule won’t leave time for marriage.”

His movie, Sincerely Yours, stank up the few theaters that bothered to show it. He never made another film. But his chance to tour Europe came in 1956 after Britain’s brand-new commercial network, ITV, began airing his old Liberace Shows. Suddenly there were new lands, with a new legion of matronly fans to wink at.

Pandemonium at Waterloo Station

Five years before Britain gave America the Beatles, we gave jolly old England Liberace. The commotion was much the same: massive screaming crowds, sold-out concerts, two highly-anticipated appearances on Sunday Night at the London Palladium, ITV’s nearly-exact equivalent to The Ed Sullivan Show. In the middle of it all was a showman who critics struggled to understand but for whom fans needed no explanation. Liberace was even set to do the Beatles one better: he was part of the line-up for the Queen’s Command Performance. Unfortunately, the Suez Crisis forced its cancellation just hours before it was set to start.

The mania began on September 25, when the Queen Mary disgorged its passengers in Southampton. Its cargo included a grand piano with a glass lid, a chandelier, two candelabras (one was a back-up), and forty trunks full of sixty suits, eighty pairs of shoes, a white jacket with a million beads, six tall coats in white, black and blue, a diamond-studded silk mohair coat, a white beaver coat and a gold lamé dinner jacket. Liberace, his mother and brother George emerged, waved to thousands gathered at the dock, took a few questions from reporters, and made their way to a special six-carriage train to London.

Thousands of mostly matronly women squealing like schoolgirls greeted the train’s arrival at Waterloo Station. A station foreman said this kind of welcome was more typically reserved for royalty. Lest royalty be offended, he quickly pointed out the critical differences: “Liberace’s got no red carpet furnished by British Railways, and there’s no potted palms either.”

Thousands of mostly matronly women squealing like schoolgirls greeted the train’s arrival at Waterloo Station. A station foreman said this kind of welcome was more typically reserved for royalty. Lest royalty be offended, he quickly pointed out the critical differences: “Liberace’s got no red carpet furnished by British Railways, and there’s no potted palms either.”

Nobody noticed the missing red carpet. Fans deluged Liberace with paper rose petals as he walked on the platform. Fifty bobbies strained to hold back the crowd as Liberace and his party made their way to two waiting Daimlers. The cars, attended by chauffeurs and footmen, were just like the ones Buckingham Palace used. So there was that.

“This Fruit-Flavored, Mincing, Heap of Mother Love”

Off in one corner of the station, a small contingent of boys and young men booed and waved banders reading “We Hate Liberace.” They weren’t alone. The next day, Daily Mirror columnist William Connor — using the pen name of of the Greek mythological prophet Cassandra — unburdened his bile duct. He began by describing a drink he had in pre-war Berlin in 1939. “Windstarke Fuenf” — Windstrength Five, a sailing term — “is the most deadly concoction of alcohol that the ‘Haus Vaterland’ can produce,” he wrote.

I have to report that Mr. Liberace, like “Windstarke Fuenf” is about the most that man can take.

But he is not a drink.

He is YEARNING-WINDSTRENGTH FIVE.

He is the summit of sex — the pinnacle of Masculine, Feminine and Neuter. Everything that He, She and It can ever want.

I have spoken to sad but kindly men on this newspaper who have met every celebrity arriving from the United States for the past thirty years.

They all say that this deadly, winking, sniggering, snuggling, chromium-plated, scent-impregnated, luminous, quivering, giggling, fruit-flavored, mincing, ice-covered heap of mother love has had the biggest reception and impact on London since Charlie Chaplin arrived at the same station, Waterloo, on September 12, 1921.

This appalling man — and I use the word appalling in no other than its true sense of “terrifying” — has hit this country in a way that is as violent as Churchill receiving the cheers on V-E Day. He reeks with emetic language that can only make grown men long for a quiet corner, an aspidistra, a handkerchief, and the old heave-ho.

Without doubt, he is the biggest sentimental vomit of all time.

Slobbering over his mother, winking at his brother, and counting the cash at every second, this superb piece of calculating candy-floss has an answer for every situation.

…Nobody since Aimee Semple MacPherson has purveyed a bigger, richer and more varied slag-heap of lilac-covered hokum.

Nobody anywhere ever made so much money out of high speed piano playing with the ghost of Chopin gibbering at every note.

There must be something wrong with us that our teenagers longing for sex and our middle-aged matrons fed up with sex alike should fall for such a sugary mountain of jingling claptrap wrapped up in such a preposterous clown.

Cassandra’s blast reverberated around the world. Chicago Daily News correspondent Ernie Hill reprinted most of Cassandra’s screed, which got fed through the paper’s wire services to other newspapers across North America. Other news stories about the controversy over Cassandra’s column repeated those passages again. You know, for context. Before the week was out, hundreds of newspapers had printed highlights of Cassandra’s diatribe under one guise or another.

Liberace told reporters that Cassandra’s “vulgarity and underlying degenerate tone” shocked him to the core. But worse, the column had a terrible effect on his dear mother:

My poor mother, a simple sweet person, was exposed to these articles and has been confined to bed and has needed medical attention ever since. My mother, who arrived in England with such a light heart, told me: “I should have stayed at home.”

Liberace’s first London concert took place on September 30. It was for a live broadcast of Sunday Night at the London Palladium. After Liberace completed his afternoon rehearsals, a crowd of unruly teenagers outside the theater prevented him from leaving. He was forced to hole up in the theater for seven hours until the show. That night, he dedicated his under-four-minute “Warsaw Concerto” to his mom, now sufficiently recovered and sitting in the balcony. She threw kisses to her son.

But controversy continued to dog Liberace’s tour wherever he went. Pickets greeted him outside the Royal Festival Hall the next evening. Inside, Liberace went on before a packed house of 4,000 as though nothing was wrong, The Guardian’s Bernard Lewis wrote: “I was in the presence of a man who did not care how silly, how awful he looked and sounded, provided only that the adolescent girls, the middle-aged matrons, and the sprinkling of very queer-looking men rolled up, paid at the doors, and yelled the place down.”

Things got rougher at a concert at Sheffield City Hall. ITV’s signal hadn’t yet reached Sheffield, so Liberace’s fame there was more by word-of-mouth. The hall still managed to sell out. But local university students heckled his concert with cries of “queer!” On October 17, Liberace returned to London for an engagement at Royal Albert Hall. The next day, Cassandra got one last dig in:

In their daily programme of events called “To-day’s Arrangements” The Times was yesterday at its impassive unsmiling best. It said:

“St. Vedast’s, Forrest Lane: Canon C.B. Mortlock, 12:30. St. Paul’s, Covent Garden: The Rev. Vincent Howson, 1:15. St. Botolph’s, Bishipsgate: Preb. H.H. Treacher, 1:15. All Souls, Langham Place: Mr. H.M. Collins 12:30.

“Albert Hall: Liberace, 7:30.”

Rarely has the sacred been so well marshalled alongside the profane.

Later that day, Liberace’s attorney in Los Angeles announced an immediate libel action against the Mirror.

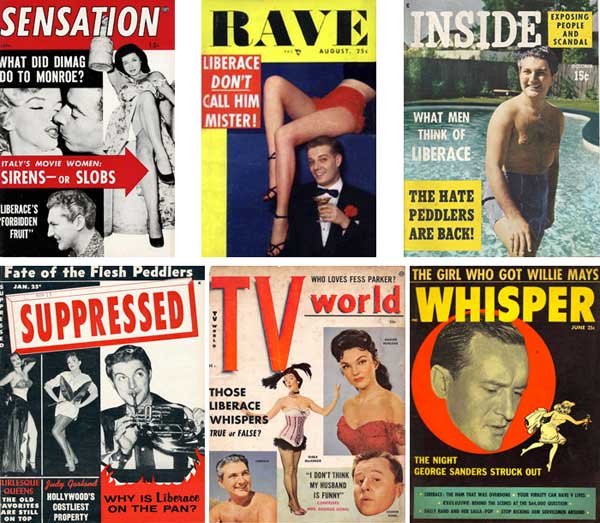

From Whispers to a Shout

Bottom: Suppressed (Jan 1955); TV World (Dec 1955); Whisper (Jun 1956).

Cassandra was far from the first to publicly impugn Liberace’s manhood. A number of critics and scandal magazines had long commented on his flamboyant outfits, lilting voice, fluttering wrists and his unusual devotion to mom. In early 1954, Sensation played on the rumors by teasing his “forbidden fruit.” It turns out the “forbidden fruit” were the two things denied him: music critics’ approval and a happy wife — he’s just too busy and too too picky to marry. But the cover very cleverly played with prevailing suspicions to pump up sales. Later that year, Rave and Inside added their own insinuations, as did Suppressed in 1955.

In December 1955, TV World played on those rumors with its teaser, “Those Liberace Whispers — True of False?” Maybe the ad for Liberace’s self-help book, The Magic of Believing, running in that issue influenced the answer. “It’s a crying shame that Liberace is the butt of jokes and sly innuendos,” wrote Peter Cored, before debunking “all the rumors” that made his cover story possible.

But six months later, in an issue that came out about a month before Liberace took off for London, Whisper raised the bar:

He loves to deck himself out in manly attire such as white fur coats and sequined dinner jackets. The wave of his marcelled locks would bring titters of admiration from Antione of Paris, and when one of his lady fans squeals at him in delight, Liberace can squeal right back at her in the same register.

Up to now, Liberace’s response was to just ignore them. These were, after all, second- and third-rate magazines that almost no one took seriously. As long as the mainstream press shied away from pressing the issue too forcefully, all Liberace had to do was sit back and wait for poor circulation and bankruptcy to kill them off for good.

But Cassandra’s column, appearing as it did in a mainstream tabloid, was a turning point. To be sure, the British press was always far more opinionated and rambunctious than its American cousins. That alone probably caught Liberace off guard. But when American newspapers reprinted substantial portions of Cassandra’s column in stories about the controversy, it became a much bigger problem. Cassandra’s accusation was now in print on both sides of the Atlantic, and that ink can never be unspilled.

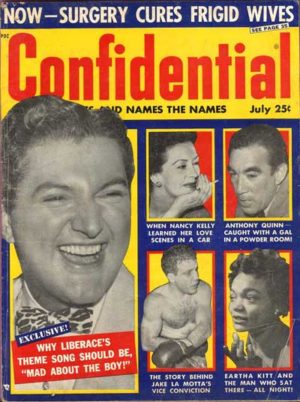

Confidential Strikes

Cassandra’s column now threatened to open the floodgates. Seven months later, on May 8, 1957,Confidential, the king of the Hollywood scandal magazines, struck hard. The semimonthly’s July issue hit the news stands with its cover story, “Why Liberace’s Theme Song Should Be ‘Mad About the Boy’.” Writer Horton Streete (probably a pseudonym) alleged that “the Kandelabra Kid” had relentlessly pursued a handsome press agent at three different hotels, in Akron, Los Angeles and again in Dallas. “The next thing the publicity man knew he was right back at it again with Liberace sitting on his lap!” wrote Streete. “A referee certainly would have penalized the panting pianist for illegal holds.”

Cassandra’s column now threatened to open the floodgates. Seven months later, on May 8, 1957,Confidential, the king of the Hollywood scandal magazines, struck hard. The semimonthly’s July issue hit the news stands with its cover story, “Why Liberace’s Theme Song Should Be ‘Mad About the Boy’.” Writer Horton Streete (probably a pseudonym) alleged that “the Kandelabra Kid” had relentlessly pursued a handsome press agent at three different hotels, in Akron, Los Angeles and again in Dallas. “The next thing the publicity man knew he was right back at it again with Liberace sitting on his lap!” wrote Streete. “A referee certainly would have penalized the panting pianist for illegal holds.”

Every word of “Mad About the Boy” was outrageous. Much of it was most likely true. Unlike other scandal magazines, Confidential’s publisher Robert Harrison was obsessed with avoiding lawsuits. He employed an army of private detectives, fact-checkers and lawyers to vet every article. Harrison believed that accuracy would be one of the magazine’s strong suits. He also had a practice of publishing less than he knew. The threat that the whole story might come out in court was often enough to deter libel suits.

That’s why Confidential’s punches landed so much harder. It was the most feared magazine in Hollywood, and the most talked about magazine in the country. Its circulation was at 4.6 million, larger than Time, which gave him the nickname “the King of Leer.” But despite the precautions, Harrison was already neck-deep in lawsuits by the time the Liberace issue came out. Liberace sued for $20 million, but he had to get in line behind Robert Mitchum, Doris Duke, Maureen O’Hara, Errol Flynn and Lizabeth Scott.

At the head of that line was the state of California. Under Attorney General Pat Brown, Confidential and its sister magazine, Whisper, were charged with conspiracy to distribute obscene material, conspiracy to commit criminal libel, and conspiracy to distribute material on abortion and male potency. (Confidential’s exposé on an abortion pill and a virility drug brought about that odd charge.) The six week trial, dubbed the “Trial of a Hundred Stars,” provided the very same prurient material Americans longed for, and that Confidential was being sued for. After the jury struggled for two weeks to agree on a verdict, it gave up, resulting in a mistrial.

Harrison had never lost a case, but the strain and legal costs were adding up. He settled with the state by paying a small fine and agreeing to change Confidential’s format away from Hollywood gossip. Harrison also settled the libel lawsuits. Liberace’s cut came to $40,000 (about $345,000 today). This meant vindication as far as Liberace was concerned.

Trial at Queens Bench IV

The Cassandra/Daily Mirror case finally reached a London courtroom in 1959. Their defense was not that Liberace was gay, but that Cassandra’s column didn’t say he was. Instead, they claimed that it fell under the defense of fair comment. This made Liberace’s offense doubly difficult. He had to first prove that Cassandra had actually made an assertion of fact and not opinion, while also convincing the jury that Liberace wasn’t gay.

The trial began on June 8. Gilbert Beyfus, Queen’s Counsel (Q.C.) for Liberace, described Cassandra as “a literary assassin who dips his pen in vitriol, hired by this sensational newspaper to murder reputations.” He repeated Cassandra’s words: that Liberace was “everything that he, she, and it can ever want.” He pointed out that the words were so integral to Cassandra’s thesis that they were included in an illustrated pull-quote at the top of the column. Beyfus said those words were “as clear as clear can be. Otherwise, I venture to suggest the words have no meaning at all.”

Liberace took the stand for three hours. After going over Liberace’s biography and details of his early career, Beyfus came straight to the point. “Are you a homosexual?”

“No, sir,” replied Liberace.

“Have you ever indulged in homosexual practices?”

“No sir, never in my life”

“What are your feelings about it?”

“My feelings are the same as anyone else’s. I am against the practice because it offends convention and offends society.”

This, of course, is perjury. Gerald Gardiner, Q.C. for Cassandra and the Daily Mirror, objected, not because Liberace lied, but because the question was irrelevant. Gardiner repeated the defense that the article made no such accusation. He also claimed, rather incredibly, that no one in their right mind could possibly read such an accusation into it. But Liberace countered that soon after Cassandra’s column appeared, “when I went on the stage (at Sheffield), there were cries from the audience of ‘queer’ and ‘fairy’ and such things as “go home, queer.”

In response to another question, Liberace claimed, “No one has ever intimated that I was a homosexual before this reporter accused me in his article so brilliantly and viciously.” Before Gardiner could continue with his questioning, Liberace addressed the jury directly: “Members of the jury, I am a performer who travels in all parts of the world. On my word of God, on my mother’s health which is so dear to me, this article means only one thing, that I am a homosexual, and that is why I am in the court.”

Word By Word

Because Cassandra’s and the Daily Mirror’s defense was that the column was fair comment, just about every word of that comment was subject to scrutiny:

Deadly. Cassandra: “he overwhelms one, he attacks the senses.” Liberace, when he is asked about comparisons with a British pianist known only as Semprini: “Evidently, he doesn’t do it quite as successfully because I have never heard of him.”

Winking, Sniggering, Giggling and Snuggling. Cassandra: “I have read a number of reports which contained these adjectives and I have observed him doing these very things on television.” Liberace: “I have tried in all my performances to inject a note of sincerity and wholesomeness because I am fully aware of the fact that my appeal on television and personal appearances is aimed directly at the family audience.”

Chromium-Plated. Cassandra: “He seems to have these light-reflecting surfaces such as a completely white suit of tails, a candelabra, an enormous ring on his finger.” Liberace, on the first time he wore a white suit: “I was greeted by an ovation when I walked on the stage and I was referred to in the newspapers as ‘Mr. Showmanship’. … This meant that…I had to dress better than the others who were copying me. One was a young man named Elvis Presley, who was coming up at the time.”

Scent-Impregnated. Cassandra: “The question of scent has been mentioned in previous reports in the Daily Mirror, Daily Express and Evening Standard.” Liberace: “I do not use scent, but I do use aftershave lotions, deodorants and eau de cologne. All well-groomed men do.”

Fruit-Flavoured. Cassandra: “That was part of the impression of confectionery which Mr. Liberace conveyed to me. Over sweetened, over-flavoured, over-luscious and just sickening.” Liberace countered that the expression is commonly directed to homosexuals. “People in England and in all parts of the world where I am dependent on making a livelihood have given it that interpretation. … Fruit-flavoured, masculine, feminine and neither — all this points to one horrible fact which has damaged my career and my reputation.” Cassandra, again: “I am well acquainted with many hostile words, including those imputing homosexuality, but I did not know that ‘fruit’ was one of them. It came as a bit of surprise to me.”

Heap of Mother Love: Cassandra: “When I see this on the stage of the London Palladium by a forty-year-old man in company with his mother, whom he may well love, I regard that as profane and wrong.” Liberace: “She is extremely proud of her children. Perhaps a bit more proud of me.”

The trial paused at the end of Thursday, June 11, and wouldn’t resume until the following Monday. The judge cautioned the jury against watching Liberace’s televised performance on the season finale of Sunday Night At the London Palladium — a tall ask for such a popular program. All week long, British papers had carried the trial’s every twist and turn, many of them reproducing pages upon pages of transcripts. Even in the Daily Mirror’s extensive coverage, Liberace came off as sympathetic and aggrieved, while Cassandra only added to his dour and caustic image. When Liberace completed his first solo number at the Palladium, the audience rewarded him with a full minute of sustained applause and cheers.

The trial resumed on Monday with more testimony from a variety of witnesses. Summing-up and jury instructions were given on Tuesday. The jury deliberated for three and a half hours before returning a verdict. They found Cassandra and the Daily Mirror guilty of libel. Damages were assessed at £8,000, or US$22,400 (about £176,000, or US$250,000 today.) UPI reported that “the curly-haired entertainer smiled weakly after the decision was announced.”

Traffic on the Strand outside the Royal Courts of Justice came to a standstill as a crowd of fans and reporters swarmed the entrance to congratulate the hero of the hour. When Liberace emerged, he had regained his famous smile to cheers of “well done” and “jolly good.” He said little as police escorted him to a waiting limousine which carried him off to the Savoy Hotel.

Traffic on the Strand outside the Royal Courts of Justice came to a standstill as a crowd of fans and reporters swarmed the entrance to congratulate the hero of the hour. When Liberace emerged, he had regained his famous smile to cheers of “well done” and “jolly good.” He said little as police escorted him to a waiting limousine which carried him off to the Savoy Hotel.

“I Felt So Sorry For Him.”

The Daily Herald noticed that the jury’s verdict “was disclosed in the High Court yesterday three minutes before it should have been — by a woman juror.” As the jury filed into the courtroom, the widowed Mrs. Jean Friend “smiled broadly at Liberace, smiled several times and gave a broad wink. Then she mouthed silently: ‘It’s all right’.” After the trial, she went to the Savoy — the same hotel where Liberace was staying — for tea with friends. A reporter followed:

The Daily Herald noticed that the jury’s verdict “was disclosed in the High Court yesterday three minutes before it should have been — by a woman juror.” As the jury filed into the courtroom, the widowed Mrs. Jean Friend “smiled broadly at Liberace, smiled several times and gave a broad wink. Then she mouthed silently: ‘It’s all right’.” After the trial, she went to the Savoy — the same hotel where Liberace was staying — for tea with friends. A reporter followed:

Liberace? I do wish him the best of luck with all my heart. I like him very much. I felt so sorry for him all the way through the case. I felt for him all the time. I never wavered for a minute from the second I sat down. Afterwards I wanted to shake his hand and congratulate him. In the court corridor he told me: ‘Thank you very much.'”

She tried to get tickets for his show, but the receptionist said that Liberace wasn’t taking any calls.

The Show Went On

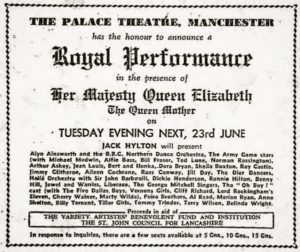

Liberace embarked on a another mini-tour of Britain, although this time press attention was much more muted now that the trial was over. One stop was in Manchester, where he was part of a very crowded bill for a charity Royal Performance for the Queen Mother. This time, there was no Suez Crisis to interrupt the show. But after three years, Liberace’s sartorial statement was no longer cutting edge. The Stage informed its readers that, early in the program:

Liberace embarked on a another mini-tour of Britain, although this time press attention was much more muted now that the trial was over. One stop was in Manchester, where he was part of a very crowded bill for a charity Royal Performance for the Queen Mother. This time, there was no Suez Crisis to interrupt the show. But after three years, Liberace’s sartorial statement was no longer cutting edge. The Stage informed its readers that, early in the program:

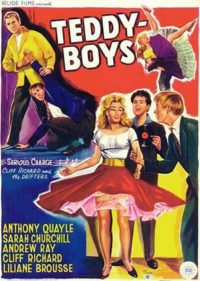

The lights went up to reveal Harry Robinson conducting Lord Rockingham’s XI in “shocking pink” suits. The Dallas Boys in black and the Vernons Girls in multi-coloured frocks got into the groove with the “Strings of My Heart” and “Don’t Look Now” before Marty Wilde — in gold lamé jacket, and Cliff Richard, idols of the fans who were staging demonstrations in the street outside, put over their own special lines.

Comedian Arthur Askey came out with a miniature piano topped with a hurricane lamp. “You’ve got to have a gimmick and I can’t afford a candelabra.” Liberace may have been upstaged a bit, but he still worked his magic. His suit with diamond buttons and sequined vest was, he explained, “one of those that all the fuss was about.” His Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat came in at four minutes flat, as always. The Manchester Guardian said he got the loudest applause of the evening. Once you have a formula that works, why would you ever change it?

Comedian Arthur Askey came out with a miniature piano topped with a hurricane lamp. “You’ve got to have a gimmick and I can’t afford a candelabra.” Liberace may have been upstaged a bit, but he still worked his magic. His suit with diamond buttons and sequined vest was, he explained, “one of those that all the fuss was about.” His Tchaikovsky Piano Concerto No. 1 in B flat came in at four minutes flat, as always. The Manchester Guardian said he got the loudest applause of the evening. Once you have a formula that works, why would you ever change it?

Epilogue:

Liberace’s much-publicized victory did little to quell the rumors, but newspapers were much more cautious about what they put into print. Today, of course, we know what was true all along: he was as gay as gay could be. But in the 1950s and 1960s, such an admission was box office poison.

Liberace’s much-publicized victory did little to quell the rumors, but newspapers were much more cautious about what they put into print. Today, of course, we know what was true all along: he was as gay as gay could be. But in the 1950s and 1960s, such an admission was box office poison.

But even if he had managed to work out a Noël Coward-like accommodation, there was now another complication. Liberace perjured himself when he testified in London and denied his homosexuality. He also most likely perjured himself in Los Angeles when he testified before a grand jury investigating Confidential. And having successfully sued Confidential and Daily Mirror, he would now be liable for far greater civil damages than he won in either case if the truth came out.

And so he steadfastly denied his sexuality throughout his lifetime. And yet, he all but dared anyone to state simply what they plainly saw. Liberace died in 1987, and for years afterwards, his estate and many of his remaining fans tried to deny the coroner’s report that it was AIDS that killed him. The Daily Mirror’s headline had the last word though: “Any Chance of a Refund?”

On the Timeline:

![]() June 17, 1959: Liberace wins his libel case against the Daily Mirror.

June 17, 1959: Liberace wins his libel case against the Daily Mirror.

Periscope:

For September 26, 1956:

Headlines: British Army Reservists are being called up for a possible response to Egypt’s seizure of the Suez Canal. Tense negotiations over the Suez Crisis continues at the U.N. Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies urges the Commonwealth to forcefully unite with Britain against Egypt. Thousands of ecstatic fans greet Liberace at Southampton and London. Electricians at the Standard Motor Company works in Coventry go on strike, forcing the idling of 5,000 workers. The Bolshoi Ballet considers coming to London. Bread prices rise as a government subsidy ends.

Headlines: British Army Reservists are being called up for a possible response to Egypt’s seizure of the Suez Canal. Tense negotiations over the Suez Crisis continues at the U.N. Australian Prime Minister Robert Menzies urges the Commonwealth to forcefully unite with Britain against Egypt. Thousands of ecstatic fans greet Liberace at Southampton and London. Electricians at the Standard Motor Company works in Coventry go on strike, forcing the idling of 5,000 workers. The Bolshoi Ballet considers coming to London. Bread prices rise as a government subsidy ends.

On the radio (UK): “Lay Down Your Arms” by Anne Shelton, “Que Sera Sera” by Dorris Day, “Rockin’ Through the Rye” by Bill Haley and his Comets, “The Yong Tong Song/Bloodnok’s Rock ‘N’ Roll Call” by the Goons, “The Great Pretender/Only You” by the Platters, “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” by Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, “Sweet Old-Fashion Girl” by Teresa Brewer, “Walk Hand in Hand” by Tony Martin, “Bring a Little Water Sylvie” by Lonnie Donegan, “Mountain Greenery” by Mel Torme, “Hound Dog” by Elvis Presley.”

On the radio (UK): “Lay Down Your Arms” by Anne Shelton, “Que Sera Sera” by Dorris Day, “Rockin’ Through the Rye” by Bill Haley and his Comets, “The Yong Tong Song/Bloodnok’s Rock ‘N’ Roll Call” by the Goons, “The Great Pretender/Only You” by the Platters, “Why Do Fools Fall In Love” by Frankie Lymon and the Teenagers, “Sweet Old-Fashion Girl” by Teresa Brewer, “Walk Hand in Hand” by Tony Martin, “Bring a Little Water Sylvie” by Lonnie Donegan, “Mountain Greenery” by Mel Torme, “Hound Dog” by Elvis Presley.”

On television: Sunday Night at the London Palladium (ITV), Take Your Pick (ITV), Double Your Money (ITV) Saturday Showtime (ITV), The Roy Rogers Show (ITV), Highland Fling (BBC), I Love Lucy (ITV). Boxing (BBC), The Adventures of Robin Hood (ITV), Movie Magazine (ITV), Hancock’s Half Hour (BBC).

On television: Sunday Night at the London Palladium (ITV), Take Your Pick (ITV), Double Your Money (ITV) Saturday Showtime (ITV), The Roy Rogers Show (ITV), Highland Fling (BBC), I Love Lucy (ITV). Boxing (BBC), The Adventures of Robin Hood (ITV), Movie Magazine (ITV), Hancock’s Half Hour (BBC).

For June 17, 1959:

Headlines: Royal Ascott begins its annual four days of racing and fashion. Court awards Liberace £8,000 in damages. General work stoppage in the printing trades to begin tonight. Labor dispute at Triumph idles 4,700 workers. Ten thousand more poised to strike at Standard Motors over redundancies. Labour party struggles to bridge the pro-H-Bomb and anti-H-Bomb wings. Federation of British Industries endorse a free trade arrangement with seven European countries as a first step toward expanding the Common Market

Headlines: Royal Ascott begins its annual four days of racing and fashion. Court awards Liberace £8,000 in damages. General work stoppage in the printing trades to begin tonight. Labor dispute at Triumph idles 4,700 workers. Ten thousand more poised to strike at Standard Motors over redundancies. Labour party struggles to bridge the pro-H-Bomb and anti-H-Bomb wings. Federation of British Industries endorse a free trade arrangement with seven European countries as a first step toward expanding the Common Market

On the radio (UK): “A Fool Such as I” by Elvis Presley, “Roulette” by Russ Conway, “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” by Buddy Holly, “It’s Late” by Ricky Nelson, “Dream Lover” by Bobby Darin, “I’ve Waited So Long” by Anthony Newley, “Side Saddle” by Russ Conway, “A Teenager In Love” by Marty Wilde, “I Go Ape” by Neil Sedaka, “Come Softly to Me” by Frankie Vaughan and the Kaye Sisters.

On the radio (UK): “A Fool Such as I” by Elvis Presley, “Roulette” by Russ Conway, “It Doesn’t Matter Anymore” by Buddy Holly, “It’s Late” by Ricky Nelson, “Dream Lover” by Bobby Darin, “I’ve Waited So Long” by Anthony Newley, “Side Saddle” by Russ Conway, “A Teenager In Love” by Marty Wilde, “I Go Ape” by Neil Sedaka, “Come Softly to Me” by Frankie Vaughan and the Kaye Sisters.

On television: Wagon Train (ITV), Play of the Week (ITV), The Army Game (ITV), Spot the Tune (ITV), Sunday Night at the London Palladium (ITV), Emergency Ward 10 (ITV), Take Your Pick (ITV), Double Your Money (ITV), The Jack Hylton Monday Show (ITV), Juke Box Jury (BBC).

On television: Wagon Train (ITV), Play of the Week (ITV), The Army Game (ITV), Spot the Tune (ITV), Sunday Night at the London Palladium (ITV), Emergency Ward 10 (ITV), Take Your Pick (ITV), Double Your Money (ITV), The Jack Hylton Monday Show (ITV), Juke Box Jury (BBC).

Sources:

In chronological order:

Before Liberace’s 1956 trip to Britain:

Bob Thomas/AP “Hollywood wonders: Will Liberace get married?” Tucson Daily Citizen (October 6, 1954): 18.

Aline Mosby/UPI. “Liberace stands firm against weepy females.” San Mateo (CA) Times (October 13, 1954): 22.

During Liberace’s 1956 trip to Britain:

Reuters. “Isn’t he gorgeous? British women fans mob Liberace.” Baltimore Evening Sun (September 25, 1956): 3.

“Our London correspondent.” The Manchester Guardian (September 25, 1956): 6.

Cassandra (William Connor). “Yearn-Strength Five.” Daily Mirror (London, September 26, 1956): 6.

Ernie Hill. “London press has field day over Liberace.” Oakland Tribune (September 26, 1956): 3.

Associated Press. “Liberace ired by British press ‘unmanly’ jibes.” Oakland Tribune (September 30, 1956): 14-A.

Reuters. “Liberace plays in London.” The New York Times (October 1, 1956): 31.

Betty Smith. “Liberace trapped by hordes of girls.” Daily Mirror (London, October 1, 1958): 1.

“Television notes: The capers of Liberace. A Stagy Appearance.” The Manchester Guardian (October 1, 1956): 5.

Bernard Levin. “The clowning of Liberace.” The Manchester Guardian (October 2, 1956): 12.

Reuters. “Liberace plays in London.” The New York Times (October 3, 1956): 66.

Art Buchwald. “British newspaper jibes shock, embitter Liberace.” Oakland Tribune (October 12, 1956): 31.

Cassandra (William Connor). “Calling all cussers.” Daily Mirror (London, October 18, 1956): 6.

Associated Press. “Liberace to sue London paper; He ‘ain’t kidding.'” Oakland Tribune (October 18, 1956): 23.

Gossip magazines and the Confidential Scandal:

“Liberace’s forbidden fruit.” Sensation (January 1954): 36-39.

Peter Corde. “Those Liberace whispers — true or false?” TV World (December 1955): 30-31, 64-66.

Sylvia Tremaine. “This month’s candidate for The Pit. Liberace: The ham that was overdone.” Whisper (June 1956): 26-27, 62-65.

Horton Streete. “Why Liberace’s theme song should be ‘Mad About the Boy’.” Confidential (July 1957): 16-21, 59-60.

“Confidential pays Liberace.” The New York Times (July 16, 1958): 25.

Henry E. Scott. Shocking True Story: The Rise and Fall of Confidential, “America’s Most Scandalous Scandal Magazine”. (New York: Pantheon Books, 2010).

1959 Trial Coverage and Aftermath:

“The Man Behind the Candelabra.” The Manchester Guardian (June 9, 1959): 3.

Howard Johnson. “Questions about a TV talk and Princes Margaret.” Daily Mirror (London, June 9, 1959): 1.

“Liberace v. Cassandra: ‘Vicious and Violent’.” Daily Mirror (London, June 9, 1959): 11-13, 16.

“Drinks On the ‘Mirror’ After Cassandra’s Remarks.” The Manchester Guardian (June 10, 1959): 6.

“Liberace v. Cassandra: I don’t trade on my sex appeal.” Daily Mirror (London, June 10, 1959): 11-13, 17.

Howard Johnson. “Cassandra: I Write What I Believe.” Daily Mirror (London, June 11: 1959): 1, 3-6.

“Cassandra defines his terms.” The Manchester Guardian (June 11, 1959): 3.

“Liberace v. Cassandra: ‘I don’t detest Mr. Liberace…'” Daily Mirror (London, June 12, 1959): 11-13.

“Liberace a ‘preposterous clown’ says columnist.” Daily Herald (London, June 12, 1959): 5.

Associated Press. “Liberace wins loud cheers on British TV.” Los Angeles Times (June 15, 1959): 7.

“Cassandra’s freedom to express his views: Not regarded as circulation raiser.” The Manchester Guardian (June 16, 1959): 3.

“Five questions the Liberace jury must face today.” Daily Herald (London, June 17, 1959): 5.

“Limit to the Jury’s discretion.” The Manchester Guardian (June 18, 1959): 3.

Howard Johnson. “£8,000.” Daily Mirror (June 18, 1959): 1.

Sidney Williams, Gerard Kemp, and Robert Adam “Woman in Liberace jury sensation: ‘I felt so sorry for him’.” Daily Herald (London, June 18, 1959): 1.

“Royal Variety in Manchester. Huge crowds greet Queen Mother.” The Manchester Guardian (June 24, 1959): 16.

Frank Bruckshaw. “Manchester Royal Variety: A dazzling occasion.” The Stage (London, July 2, 1959): 3.

![[Emphasis Mine]](http://jimburroway.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/McCarthyCohn.jpg)