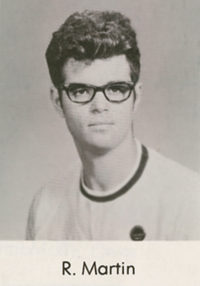

Robert Martin, Jr., enrolled at Columbia University in the fall of 1965. He was openly bisexual. His dorm suitemates reviled him because of it. The school officials’ solution was to move him out of that dorm and into a single room in another dorm.

That summer after his torturous freshman year, he met James Milham, a Columbia senior, while on Fire Island. The two became fast friends. Not long after school started again in the fall, Martin and Milham discussed the homophile movement over coffee. Martin thought about his freshman year at Columbia and decided it could sure use some kind of a campus Mattachine Society. The club would be a political and educational group. But it could also provide a gay social life on campus, something that was sorely needed. Martin even dreamed that it club could someday spawn a national movement of campus gay rights groups.

Five other students had already joined Martin and Milham to form a small gay clique they called “the family.” That group became the nucleus of the Student Homophile League. They then set out to gain campus recognition as a student group. The requirements were simple: all they had to do was submit a copy of their bylaws, and the names of four officers and one regular member.

The Struggle for a Charter

Both Martin and Milham were game. But first, Martin had to do something about his name. It was one thing to sign his name as an officer for the group, but quite another to publicly use that same name as its leader. He had the same fears as everyone else. They all wanted careers after college, and nobody wanted trouble from the police, the FBI, or fellow students. Besides that, Robert Martin., Jr.’s father, Robert Martin, Sr., taught mathematics at Rider College, just a little ways down the New Jersey Turnpike near Trenton. Robert Martin, Jr., couldn’t be openly bi without causing problems for Robert Martin, Sr., but Stephen Donaldson could. Martin chose that name based on his first love in high school, a baseball player named Donald.

But the rest of the group refused to submit their names. Donaldson and Milham were undeterred. They submitted the paperwork, clearly spelling out the group’s goals, along with a statement explaining why they could only submit a partial roster.

As expected, Columbia rejected the applications. Donaldson reached out to gay rights activist Foster Gunnison, a Columbia alumnus, for advice. Gunnison had been the driving force behind the creation of the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations (NACHO). Together, they hit on a plan. When Columbia rejected the application, the stated reason had nothing to do with having a homosexual group on campus. The rejection was based solely on the incomplete roster. If Donaldson could fix that problem, then Columbia would have no choice but to accept the application. Columbia couldn’t very well object to the group’s mission now after they had been silent about it the first time around.

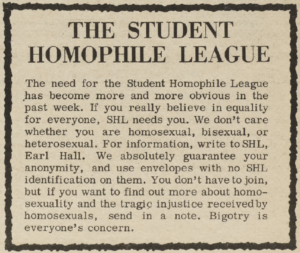

Donaldson found a few straight and prominent campus leaders willing to become pro forma members as a way of asserting civil liberties for all students. This meant that now there was a roster that met the school’s requirements. It also meant that if Columbia did try to protest the group’s mission and composition, they couldn’t. It was no longer just a gay group. It worked. On April 19, 1967, the Student Homophile League became the first gay student organization to be officially recognized by an American university.

“Decent and Respectable”

That recognition came with expectations, mainly that SHL would maintain a low profile. Donaldson had set that expectation during the application process. He assured school officials that SHL would focus on “correspondence, academic research, white papers, newsletters and the like.” There would be no picketing, no rabble-rousing, no overt activism. Just quiet intellectual and educational pursuits. “Because we do not court public exposure of our identity — such exposure would ruin our lives and our careers — we have little interest in such activities…,” the application read.

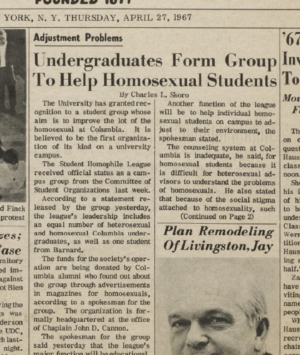

Donaldson began breaking that promise almost immediately. He sent a flurry of press releases to several large newspapers, wire services and magazines. The charter was just a week old when The Columbia Daily Spectator announced the new group on its front page. It’s a curious article. It names no names. The only person quoted — and he was quoted extensively — was “the spokesman.”

Well, the article did name one individual: Chaplain John D. Cannon, the Episcopal priest who allowed SHL to use his office as their headquarters. The article didn’t sit well with Cannon, who criticized the League for publicizing their group too aggressively. “A press release can be an invitation to repression,” he said. He also expressed his misgivings about the group’s plans to provide support for gay students because, so he claimed, not all homosexuals wanted social approval.

The Spectator’s editorial on April 28, the day after SHL’s public debut, illustrated the challenges they were up against, even among some of the most liberal students on campus. “Sexual taboos,” it read “… have been under attack in recent years, with encouraging results. In the arts, in law, in theology, even in the staunch bastion of ‘community standards,’ the forces of priggishness and prudery have found it increasingly difficult to defend themselves… The results of the so-called ‘sexual revolution’ have been highly beneficent.”

After cheering the assaults on the sexual ramparts, the Spectator welcomed the Student Homophile League with much more muted tones: “The League… has wisely decided to make its major function an educational one, and will not attempt to improve the personal relations of its members, or to act as a social club.” Its goals, therefore, were “decent and respectable ones.” Think about it. This was 1967. The sexual revolution was in full flower. The Summer of Love was just weeks away. Priggishness may have been out of fashion elsewhere on campus, but it was still expected of SHL.

The News Spreads Nationwide

News of SHL soon spread beyond the campus. “Columbia Charters Homosexual Group,” read the front page headline in the May 3rd New York Times. “We wanted to get the academic community to support equal rights for homosexuals,” it quoted Donaldson. The Times article went nationwide through its in-house wire service, ensuring its appearance in hundreds of papers. Most ran it under positive or neutral headlines. The conspicuous exception was the Gainesville (Florida) Sun. Its headline ran, “Student Group Seeks Rights for Deviates.” But Time magazine treated the whole thing with a literary yawn:

While declining to identify himself or other members by name (“We would be losing jobs for the rest of our lives”), the league’s chairman insists the group is educational, not social, and “plans no mixers with Harvard.” So far, Columbia students seem little interested in joining. Shrugged Sophomore Elliot Stern: “As long as they don’t bother the rest of us, it’s O.K.” The league’s biggest problem will probably be its self-imposed secrecy. As some students asked: How do you treat them equally when you don’t know who they are?

Campus Backlash

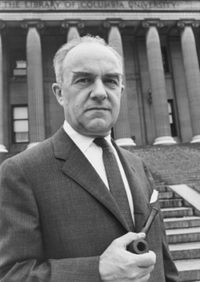

Columbia Dean David B. Truman was unhappy with all of this publicity. Named to the post in 1962, Truman had a reputation for liberalizing the university and changing some of its outdated rules. But Truman’s relatively liberal tendencies didn’t extend to the SHL. He heard from plenty from alumni, and complained that the publicity “sure as hell won’t help” the university’s fund drive, admissions or recruiting. Once Columbia receives “bad publicity,” he said “it can never catch up.” He accused the SHL of mischaracterizing its relationship with the university. Just because Columbia issued a charter, he said, it didn’t mean it endorsed the group. He regretted the group’s formation and questioned whether they were needed on campus.

Criticisms also came from Dr. Anthony F. Philip, director of the university’s counseling service. He put his vivid imagination to work in his letter to the Spectator:

Extremist spokemen for these self-proclaimed “homosexuals” defeat their own professed purposes when they show the very same sorts of prejudice they deplore in others. To type-cast as villain and adversary the heterosexual who is “straight” implies as distorted a picture of reality as the view of those who see only “fairies” or “queers” instead of real people. And however justified or outraged a “homosexual” may feel, it defeats his ostensible purpose to assume all heterosexuals are bigots and to reduce the issue to the absurdity of invective or angry exhibitionism.

Philip warned that this “extremist” group would be dangerous to impressionable students. “If there is one thing such students certainly can do without,” he wrote, “it is the mythology that they really are homosexuals whose ‘latent homosexuality’ needs only to be ‘brought out’ by the sympathetic, tutorial attention of the Student Homophile League.”

“An Extremist Political Group”

The backlash also came from surprising quarters within the homophile movement. Dick Leitsch, president of the Mattachine Society of New York, was what we might today call a media whore. He was, in many ways, an effective leader of MSNY, when he wasn’t treating it as his personal fiefdom. But he was also jealous of anyone else who might steal his spotlight. That jealousy extended to the Student Homophile League. Leitsch wrote to Frank Hogan, the Manhattan District Attorney and a member of the Columbia Board of Trustees, with advice on how to undermine Donaldson:

The man using the pseudonym Stephen Donaldson is known to me and to the Mattachine Society as an irresponsible, publicity-seeking member of an extremist political group. We have grave doubts as to his sincerity in his stated aim as helping homosexuals, and feel that he may be, instead, a bigoted extremist, interested upon wrecking the homophile movement

But the Student Homophile League was here to stay, despite the efforts to throw roadblocks in its path. Columbia forbade SHL from putting on social functions, citing the state’s sodomy law. What they imagined happening in those social functions is anybody’s guess. When freshman students arrived at school the next fall after celebrating the Summer of Love, the Dean’s office blocked an SHL welcoming letter from inclusion in their orientation package. SHL apparently knew that would happen before they submitted their letter. It ended with this:

Those who feel themselves to be homosexual or bisexual or who are uncertain about their sexual orientation can expect sympathetic and confidential consideration from most of the religious counselors and the staff of the Columbia Counseling Service, as well as from the SHL itself. We cannot at this time extend that statement to the College Dean’s Office.

Epilogue:

Dean Truman became Columbia University’s vice president and provost later in 1967. He was considered the leading candidate to succeed President Grayson Kirk, who was expected to retire soon. That changed in 1968 when demonstrations rocked the campus and students “liberated” several buildings. Truman called the police to clear the buildings, resulting in several injuries. Truman and Kirk resigned in January 1969.

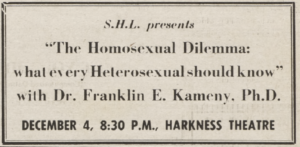

By the end of 1967, more than 20 people had joined SHL. In November, SHL sponsored a talk by gay rights activist Frank Kameny. The talk filled the 200-seat Harkness Academic Theatre, a lecture hall under the library.

Students at Stanford, the University of Pittsburgh, and Cornell soon expressed interest in starting chapters on their campuses. Cornell University was the second to establish a Student Homophile League. Famed peace and justice activist Fr. Daniel Berrigan, the associate director for service at Cornell United Religious Works, agreed to be the group’s adviser. Cornell recognized its SHL on May 9, 1968 with very little fuss.

By 1970, Columbia’s Student Homophile League had changed its name to Gay People at Columbia. In 1971, GPC began a lengthy fight against the administration to create a gay lounge in the basement of the Furnald Hall dormitory. They finally got their lounge in late November of 1972 by simply taking over a space and claiming as their own. Today, the organization is known as the Columbia Queer Alliance, and that very same lounge is still in use as the Stephen Donaldson Queer Lounge.

Donaldson became active in the North American Conference of Homophile Organizations, serving as an officer in 1969-1970. After graduating from Columbia in 1970, he joined the Navy and served mainly in the Mediterranean. He was given a general discharge once his homosexual activities became known. He then became a bisexual-rights activist, and served as chairman of the Quaker’s Committee of Friends on Bisexuality.

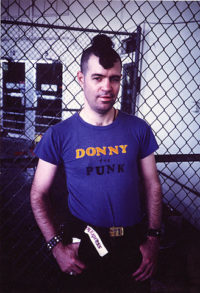

In 1973, Donaldson was arrested at a White House protest. Police threw him in a jail where as many as 45 inmates gang-raped him. As soon as he got out, he became a crusader against male-on-male rape. Unable to find effective psychotherapy — nobody recognized the trauma of male rape victims at the time — his emotional condition steadily deteriorated. He was arrested in 1976 for possession of marijuana. Instead of being raped again, he “capitulated,” and discovered the role of the jailhouse punk — an inmate who exchanges sexual favors for protection. Another 1977 drug arrest sent him to jail again, where he was once more gang-raped until guards moved him to another cell. In that cell, he embraced the nickname of “Donny the Punk.”

In 1980, Donaldson hit rock bottom. He shot up a VA hospital, angry at the difficulties he encountered trying to be treated for an STD. A court sentenced him to four years in prison for assault with intent to murder. After his release, he became director of Stop Prison Rape, Inc., and worked to help prisoners deal with the trauma of rape, and advocated for protections against it. He died of AIDS in 1996, just before his fiftieth birthday

Periscope:

Headlines for April 19, 1967: Columbia Administration denies student request to ban Marine recruitment in dorm lobby. North Vietnamese MiGs engage American Air Force in 17 separate dogfights over South Vietnam. Famine and drought sweep India’s Bihar state. Sen. Robert Kennedy blasts construction trade unions for failing to admit African-Americans. Unmanned Survey 3 lands on moon, sends back TV images to earth. At least 124 killed in Swiss airline crash in Cyprus. West Germany’s first post-war Chancellor, Konrad Adenauer, dies. Louisville, Kentucky police break up segregated housing protest using tear gas.

On the radio: “Somethin’ Stupid” by Nancy and Frank Sinatra, “Happy Together” by the Turtles, “A Little Bit of Me, A Little Bit of You” by the Monkees, “I Think We’re Alone Now” by Tommy James and the Shondells, “Western Union” by the Five Americans, “This is My Song” by Petula Clark, “Sweet Soul Music” by Arthur Conley, “Bernadette” by the Four Tops, “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” by Aretha Franklin, “Jimmy Mack” by Martha and the Vandellas.

On the radio: “Somethin’ Stupid” by Nancy and Frank Sinatra, “Happy Together” by the Turtles, “A Little Bit of Me, A Little Bit of You” by the Monkees, “I Think We’re Alone Now” by Tommy James and the Shondells, “Western Union” by the Five Americans, “This is My Song” by Petula Clark, “Sweet Soul Music” by Arthur Conley, “Bernadette” by the Four Tops, “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” by Aretha Franklin, “Jimmy Mack” by Martha and the Vandellas.

On television: Bonanza (NBC), The Red Skelton Hour (CBS), The Andy Griffith Show (CBS), The Lucy Show (CBS), The Jackie Gleason Show (CBS), Green Acres (CBS), Beverly Hillbillies (CBS), Daktari (CBS), Bewitched (ABC), The Virginian (NBC), Gomer Pyle, USMC (CBS), The Fugitive (ABC), Get Smart (NBC), Star Trek (NBC), My Three Sons (CBS), Family Affair (CBS), Gilligan’s Island (CBS).

New York Times best sellers: Fiction: The Arrangement by Elia Kazan, The Secret of Santa Vittoria by Robert Crichton. Non-fiction: Madame Sarah: Sarah Bernhardt by Cornelia Otis Skinner, Everything but Money by Sam Levenson.

Sources:

Brett Beemyn. “The Silence is Broken: A History of the First Lesbian, Gay, and Bisexual College Student Groups.” Journal of the History of Sexuality 12, no. 2 (April 2003): 205-223.

Wayne R. Dynes. “Stephen Donaldson (Robert A. Martin) (1946-1996)” In Vernon L. Bullough (ed.) Before Stonewall: Activists for Gay and Lesbian Rights in Historical Context (New York: Harrington Park Press, 2002): 265-272.

David Eisenbach. Gay Power: An American Revolution (New York: Carroll & Graf, 2006): 51-79.

Arthur Kokot. “Chapters at Other Campuses Sought by Homophile League.” Columbia Daily Spectator (November 28, 1967): 1.

Anthony F. Philip. Letter to the editor: “The Homophile League.” Columbia Daily Spectator (May 9, 1967): 4.

Murray Schumach. “Columbia Charters Homosexual Group.” New York Times (May 3, 1967): 1, 40.

Charles L. Skoro. “Undergraduates Form Group To Help Homosexual Students.” Columbia Daily Spectator (April 27, 1967): 1, 2.

Charles L. Skoro. “Homophiles Denied Mailing Privileges.” Columbia Daily Spectator (September 29, 1967): 1, 3.

Daniel M. Taubnam. “Breaking the Ice: New Student League Backs Homosexuals.” Cornell Daily Sun (November 11, 1967): 8.

“Students: Equality for your fellow man.” Time (May 12, 1967). Available online with subscription here.

“Homophile League Criticized for Seeking Excess Publicity.” Columbia Daily Spectator (May 4, 1967): 1.

“Truman Questions Homophile Group’s Place at Columbia.” Columbia Daily Spectator (May 5, 1967): 1, 3.

“SCARB” Recognizes SHL.” Cornell Daily Sun (May 10, 1968): 6.

![[Emphasis Mine]](http://jimburroway.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Lesbians.jpg)