Mildred Jeter and Richard Loving were an unusual couple. They had long crossed the racial barrier as friends in rural Central Point, Virginia. She was Black and Native American, he was white. That friendship turned to dating. When Mildred became pregnant at the age of 18 in 1958, they eloped to Washington, D.C.

After returning home, police invaded their house late one night hoping to catch them in the act of having sex. That alone was a crime because of their racial differences. Mildred pointed to the marriage license hanging on the wall, believing that it would protect them.

Little did she know, but that license was proof that they had committed another crime. Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act of 1924 prohibited any “colored” person with so much as one drop of African American or Indian blood from marrying a white person. Miscegenation was a felony, punishable by a prison sentence of between one and five years. The indictment accused the Lovings of “cohabitating as man and wife, against the peace and dignity of the Commonwealth.” The couple pleaded guilty on January 6, 1959. Their one-year jail sentence was suspended for 25 years on the condition that they leave Virginia.

The Lovings moved to D.C., and in 1963, with the ACLU’s backing, they began a series of motions and lawsuits challenging Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act. The first step was to file a motion before the original judge, Leon M. Bazile, to vacate the case and reverse his ruling. He refused, writing:

The Lovings moved to D.C., and in 1963, with the ACLU’s backing, they began a series of motions and lawsuits challenging Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act. The first step was to file a motion before the original judge, Leon M. Bazile, to vacate the case and reverse his ruling. He refused, writing:

Almighty God created the races white, black, yellow, malay and red, and he placed them on separate continents. And but for the interference with his arrangement there would be no cause for such marriages. The fact that he separated the races shows that he did not intend for the races to mix.

That response served as the basis for an appeal to the Virginia Supreme Court. That court upheld the lower court’s ruling. The next step was the U.S. Supreme Court.

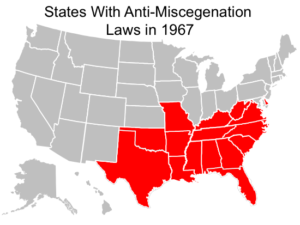

On June 12, 1967, the Supreme Court struck down Virginia’s anti-miscegenation law, along with similar laws in fifteen other states. In the unanimous ruling, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote:

Marriage is one of the “basic civil rights of man,” fundamental to our very existence and survival. … To deny this fundamental freedom on so unsupportable a basis as the racial classifications embodied in these statutes, classifications so directly subversive of the principle of equality at the heart of the Fourteenth Amendment, is surely to deprive all the State’s citizens of liberty without due process of law. The Fourteenth Amendment requires that the freedom of choice to marry not be restricted by invidious racial discrimination. Under our Constitution, the freedom to marry, or not marry, a person of another race resides with the individual and cannot be infringed by the State.

Warren specifically found that Virginia’s law was racist:

There is patently no legitimate overriding purpose independent of invidious racial discrimination which justifies this classification. The fact that Virginia prohibits only interracial marriages involving white persons demonstrates that the racial classifications must stand on their own justification, as measures designed to maintain White Supremacy.

In a separate concurring opinion, Justice Steward Potter also pointed out the racially-discriminatory dimension:

…it is simply not possible for a state law to be valid under our Constitution which makes the criminality of an act depend upon the race of the actor.

The ruling was part of a much larger change in America. It also facilitated change. In 1967, only 3% of newlywed couples were interracial. By 2015, the figure was 17%. Despite this ruling, many now-unenforceable anti-miscegenation laws remained on the books for several years to come. In 2000, Alabama voters approved a ballot initiative to repeal its anti-miscegenation law. But more than half a million — 40% — voted to keep it.

Epilogue:

Mildred and Richard were never political people. After the Supreme Court victory, the couple returned to Virginia and raised three children. Richard died in 1975 at the age of 41 when their car was struck by a drunk driver. Mildred lost her right eye in the accident. She passed away in 2008 of pneumonia at the age of 68. But a year before she died, she issued a statement on the 40th anniversary of Loving v. Virginia, in which she saw the fight for the freedom to marry as unfinished business:

My generation was bitterly divided over something that should have been so clear and right. The majority believed that what the judge said, that it was God’s plan to keep people apart, and that government should discriminate against people in love. But I have lived long enough now to see big changes. The older generation’s fears and prejudices have given way, and today’s young people realize that if someone loves someone, they have a right to marry.

Surrounded as I am now by wonderful children and grandchildren, not a day goes by that I don’t think of Richard and our love, our right to marry, and how much it meant to me to have that freedom to marry the person precious to me, even if others thought he was the ‘wrong kind of person’ for me to marry. I believe all Americans, no matter their race, no matter their sex, no matter their sexual orientation, should have that same freedom to marry. Government has no business imposing some people’s religious beliefs over others. Especially if it denies people’s civil rights.

I am still not a political person, but I am proud that Richard’s and my name is on a court case that can help reinforce the love, the commitment, the fairness, and the family that so many people, black or white, young or old, gay or straight, seek in life. I support the freedom to marry for all. That’s what Loving, and loving, are all about.

Mildred Loving passed away from pneumonia on May 2, 2008, at the age of 68. She was survived by two of her children and many grandchildren and great-grandchildren.

Periscope:

Headlines for June 12, 1967: The Six-Day War has just ended, Israel to keep West Bank, Gaza, Golan Heights, Sinai. Experts fear refugee crisis in the Middle East. Israel rejects outside negotiators for peace solution. Egypt’s President Gamal Nasser sacks twelve top military commanders. Soviet Union breaks diplomatic ties with Israel. Race rioting takes place in Tampa, Cincinnati. Task force recommends federal government regulate clean air and water. Pentagon reports 10 North Vietnamese aircraft downed, 100 enemy troops killed; 47 Marines wounded.

On the radio: “Respect” by Aretha Franklin, “Groovin'” by the Young Rascals, “I Got Rhythm” by the Happenings, “Release Me (And Let Me Love Again)” by Engelbert Humperdinck, “Him or Me — What’s It Gonna Be” by Paul Revere and the Raiders (feat. Mark Lindsay), “Somebody To Love” by Jefferson Airplane, “She’d Rather Be With Me” by the Turtles, “Little Bit O’ Soul” by the Music Explosion, “All I Need” by the Temptations, “Creeque Alley” by the Mamas and the Papas.

On the radio: “Respect” by Aretha Franklin, “Groovin'” by the Young Rascals, “I Got Rhythm” by the Happenings, “Release Me (And Let Me Love Again)” by Engelbert Humperdinck, “Him or Me — What’s It Gonna Be” by Paul Revere and the Raiders (feat. Mark Lindsay), “Somebody To Love” by Jefferson Airplane, “She’d Rather Be With Me” by the Turtles, “Little Bit O’ Soul” by the Music Explosion, “All I Need” by the Temptations, “Creeque Alley” by the Mamas and the Papas.

On television: Bonanza (NBC), The Red Skelton Hour (CBS), The Andy Griffith Show (CBS), The Lucy Show (CBS), Green Acres (CBS), Beverly Hillbillies (CBS), Daktari (CBS), Bewitched (ABC), The Virginian (NBC), Gomer Pyle, USMC (CBS), The Fugitive (ABC), Get Smart (NBC), Star Trek (NBC), My Three Sons (CBS), Family Affair (CBS), Gilligan’s Island (CBS).

New York Times best sellers: Fiction: The Eighth Day by Thornton Wilder, The Arrangement by Elia Kazan, Washington, D.C. by Gore Vidal. Non-fiction: The Death of a President, by William Manchester, Everything But Money, by Sam Levenson.

![[Emphasis Mine]](http://jimburroway.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/DoBFounders.jpg)