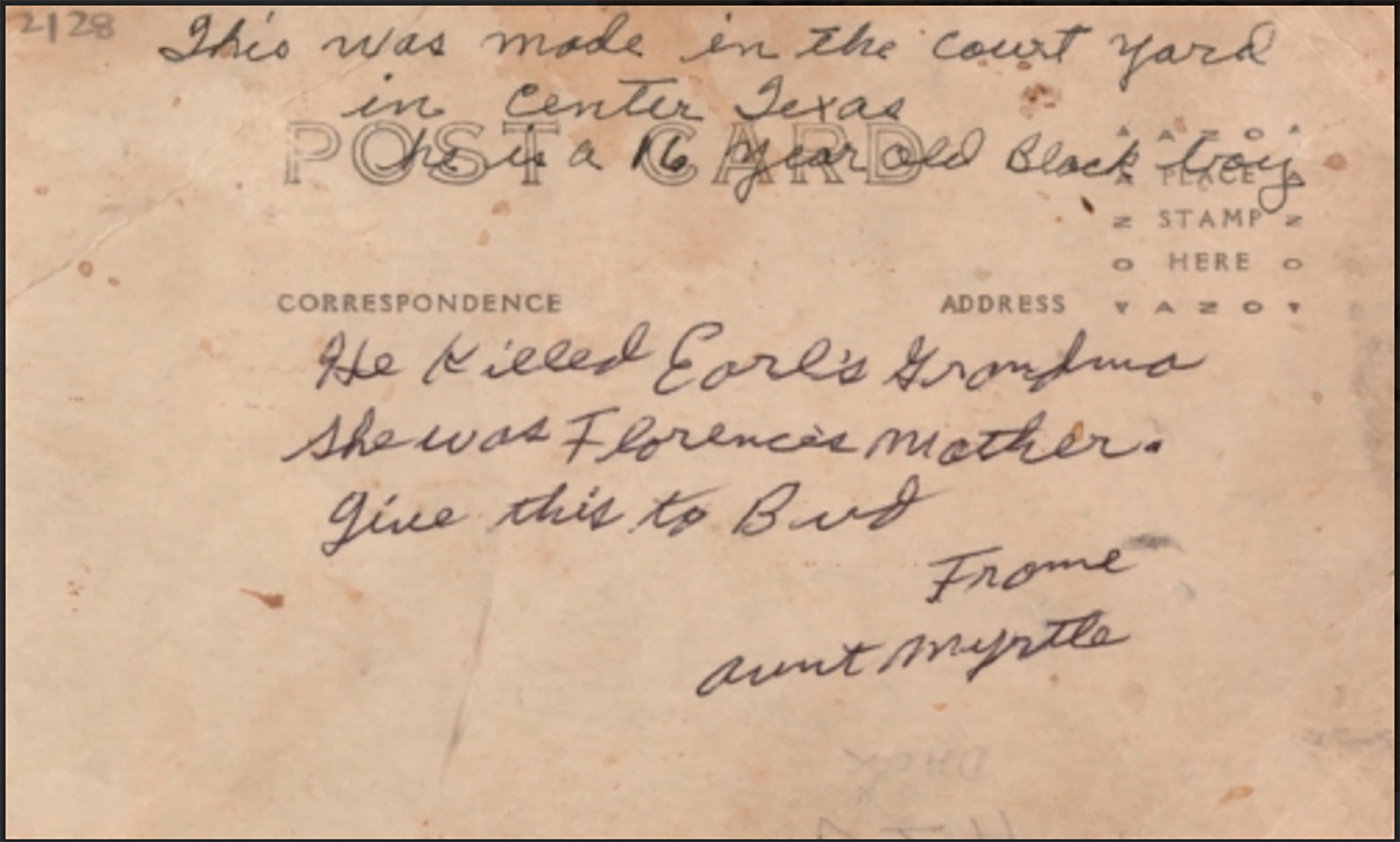

This was made in the Court Yard in Center, Texas he is a 16 year old Black boy.

He killed Earl’s Grandma. She was Florence’s mother. Give this to Bud.

From

Aunt Myrtle

Earl’s Grandma was Maggie Hall (some newspapers gave her name as Marjie), a farmer’s widow living near the small town of Center, about 35 miles northeast of Nacogdoches and not far from the Louisiana border. Center was our next stop in our road trip across the country.

When we go about our lives today and run across something we want to share, we just Instagram, Tweet, and Facebook it and we’re done. In the early twentieth century, postcards filled that role. We might remember them as souvenirs sold in gift shops to tourists. But before that, local photographers made them to commemorate special occasions in the community, Instagrammable happenings that people took part in and wanted to remember, or maybe they weren’t there and wished they had. So that’s why we find postcards of parades, carnivals, lynchings, homecomings, revivals and the like.

When we go about our lives today and run across something we want to share, we just Instagram, Tweet, and Facebook it and we’re done. In the early twentieth century, postcards filled that role. We might remember them as souvenirs sold in gift shops to tourists. But before that, local photographers made them to commemorate special occasions in the community, Instagrammable happenings that people took part in and wanted to remember, or maybe they weren’t there and wished they had. So that’s why we find postcards of parades, carnivals, lynchings, homecomings, revivals and the like.

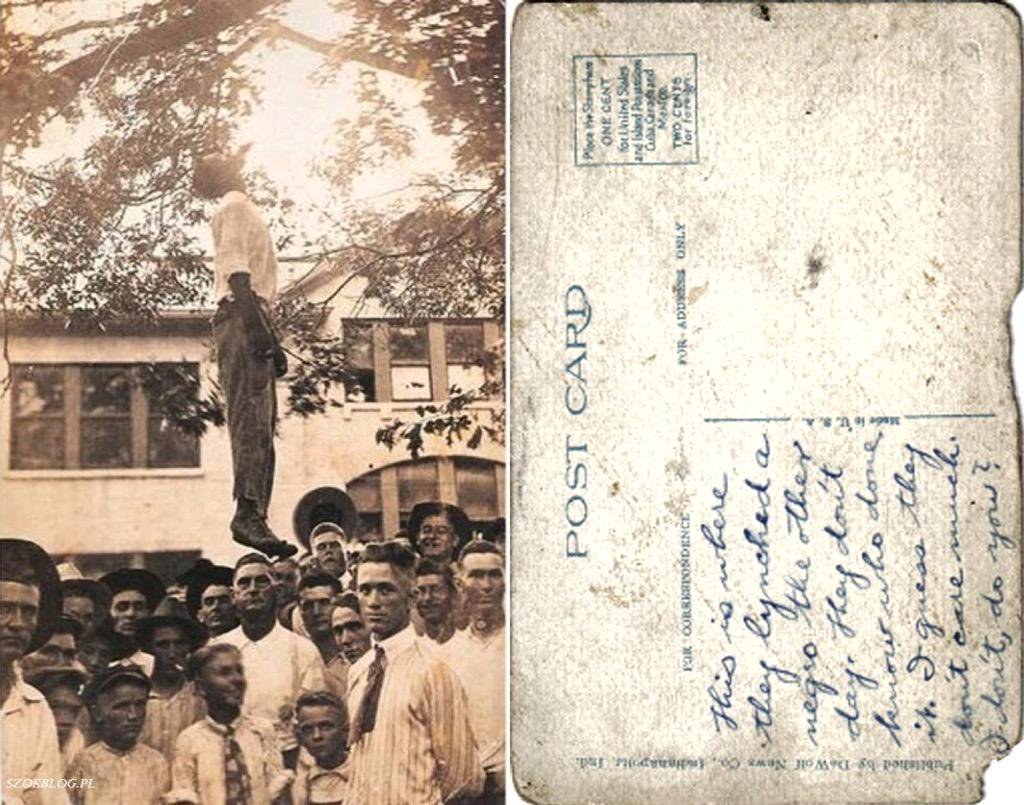

Yes, that’s right. I said lynchings, like this one that took place on August 2, 1920 in Center, Texas, which produced one of the most iconic images of lynchings in America.

Center’s population in 1920 was 1,838. If this Associated Press story is to be believed, more than half of the town’s residents turned out for the festivities:

A mob of more than 1,000 men at 3 o’clock Monday afternoon stormed the county jail, battered down the steel doors, wrecked the steel cell and took out Daniels, a negro, charged with the murder and hanged him to a limb of a tree in the court house yard.

The lynching followed announcement by officers of a full confession made for the grand jury, now in session, also to the district attorney, J.P. Anderson. Mrs. Marjie Hall, the wife of a well known farmer living near Center, was brutally attacked and later found unconscious at a lonely point near her home last Thursday night. Her skull was crushed and her body bruised and lacerated. Shw was brought to a local sanitarium where she died Friday. Lige Daniels was suspected on account of an alleged threat previously made, and after his arrest followed.

—Marshall (TX) Morning News, August 3, 1920, p1.

Accounts of lynchings like this often include assertions that the prisoner confessed to the crime he was accused of. The circumstances of such confessions are rarely described. Daniels certainly had no attorney present, and African-Americans were often given a dreadful choice: confess and we’ll protect you in jail, or claim your innocence and we’ll free you to the mob waiting outside.

The next day, Judge Spottiswood Sanders instructed a specially-convened grand jury to investigate the lynching and return indictments “against every person in any way connected with the lynching.” No indictments were ever returned, even though the man who donated the rope proudly displayed the noose on his front porch. It is said to have turned black.

And then there were the postcards. In this one, I count at least twenty-two people staring into the camera. At least four of them are children. If you look closely, you can see a few workers peering out of the courthouse annex windows. Most of those faces would have been readily familiar in such a small town. Many of those face may be familiar to some residents today. But none of them betray any trace of horror or shock. Some look solemn, they all look relaxed, even satisfied, bearing an easy nonchalance. It’s just another day.

A few are clearly having a great old time. Crop the photo just so, and you might think this was a gathering at a county fair or a church picnic. Indeed, many of them probably did attend church the day before and will do so again the following Sunday, confident in the belief that they had either done or witnessed the Lord’s work.

And above them all hangs Lige Daniels, his neck stretching skyward and his bare feet hovering just above their heads. A message scribbled on the back of this postcard seems to speak for everyone there:

This is where they lynched a negro the other day. They didn’t know who done it. I guess they don’t care much. I don’t, do you?

Eight years later, On May 14, 1928, “Buddy” Evins was arrested, charged with killing a white farmer two days earlier. Fearing for Evins’s safety in Center, the sheriff took him to San Augustine, a community twenty miles to the south with its own history with lynchings. Evins, understandably, didn’t feel much safer in San Augustine and escaped on Saturday the 19th.

His escape wasn’t discovered until the next morning. Posses went out to search for him, and he was captured early Monday morning near Timpson after a brief exchange of gunfire in which Evins was wounded in the leg.

The sheriff decided to bring Evins back to Center, despite his earlier fears of mob violence there. And sure enough, when he and the constable arrived back in Center at about 7:30 a.m. that morning, a mob of about 300 had gathered to meet them. The mob grabbed the injured Evins from the back of the truck and hustled him over to the same old oak tree in front of the courthouse annex. The branch that held Lige Daniels’s weight eight years earlier was now dead. Superstition had it that the branch was cursed because of the hanging. But it was still there, and still plenty sturdy. Someone in the mob reasoned that there was no sense in risking another branch of this magnificent tree on this negro, so they hanged Evins from the same dead branch.

According to news reports, this mob was considerably calmer, almost businesslike, when compared to the one that took Daniels. They dispersed quietly after their work was done, although onlookers remained. Evins’s dead body still hung from that dead oak branch at 9:00 a.m. as shopkeepers and businessmen arrived at the courthouse square to open for business.

The Austin American reported that the state had little interest in investigating the lynching:

The state Monday has not been asked to investigate the lynching of Buddy Evins, negro, at Center and officials indicated no administration action would be taken unless specifically requested. Neither the adjunct general’s department nor the attorney general’s office was notified officially of the affair. Gov. (Dan) Moody’s policy heretofore has precluded Texas Ranger work in community matters unless local officers confessed inability to cope along with a given situation — provided the trouble in question was not menacing.

— Austin American, May 22, 1928, p2

No photos of this second lynching have emerged, but other mementos circulated around Center. Enterprising craftsmen cut down the dead branch and made gavels out of the wood. Some of those gavels are said to still be in use in east Texas.

The old oak tree finally died in the early nineties and was removed without ceremony. A new one grows in its place.

The old oak tree finally died in the early nineties and was removed without ceremony. A new one grows in its place.

On April 4, 1964, a ceremony was held on the courthouse square for the centennial of the Texas Muster. Thirty-seven descendants participated in the roll call of soldiers who fought for the Confederacy in the Red River campaign. There’s a marker on the Courthouse square commemorating that. It stands next to another marker honoring Shelby County’s soldiers of World War I and World War II. A large granite monument in front honors “All veterans past — present — future.” Another state historical marker, erected in 1999, honors John Joseph Emmett Gibson, the architect of the eccentric 1885 courthouse building, designed to look like an Irish castle.

But there’s no marker to commemorate one of the most famous lynchings in Texas — thanks to that postcard — or the last lynching in the county. Shelby County leaders met in 2018 and decided to keep it that way. The Shelby County Commissioner’s Court debated a proposal by a Center resident Delbert Jackson to erect a historical marker at the site of the old hanging tree on the Courthouse Square to commemorate the lynchings. He was opposed by the Shelby County Historical Commission. The Historical Commission’s chairperson, Colleen Dogget, spoke on their behalf: “The courthouse is and should be the focus of our square and we do not honor a single person with a historical marker. … If we did place one we would have to honor every person who should have one on the square, and the courthouse would no longer be the focus.”

History repeats if it’s not remembered. Dogget knows this. She’s heard it a million times, and has probably said it a few. Two citizens of her community were denied justice on the very grounds of that temple of justice. Her rationale for not commemorating that fact is preposterous. It’s not the individuals’ names that’s important to remember — although Lige Daniels and Buddy Evins must never be forgotten. No, it’s the community’s barbarous actions on those two days in 1920 and 1928, that must not be forgotten. It’s the pride, and even joy for some, that they displayed while carrying out their grizzly acts that must not be ignored. It’s the ordinariness of the thing. The eagerness with which the crowd draws itself into the photographer’s lens, leaning in to make sure they’re in the shot. Look at the image again. You can still hear the young boy’ laughter under Lige Daniel’s feet.

But focus on the historic courthouse building, the Shelby County Historical Commission says. Isn’t it beautiful? It’s historic, you know, and they’re rightly proud of it. And while you’re there, feel free to read the marker and remember the sons and daughters of the Confederacy that answered a commemorative muster roll call in 1964. Just ignore the bloody patch of ground in front of the annex.

But focus on the historic courthouse building, the Shelby County Historical Commission says. Isn’t it beautiful? It’s historic, you know, and they’re rightly proud of it. And while you’re there, feel free to read the marker and remember the sons and daughters of the Confederacy that answered a commemorative muster roll call in 1964. Just ignore the bloody patch of ground in front of the annex.

But whether the people of Center like it or not, their parents and grandparents have already ensured that that patch of ground cannot be ignored. Lige Daniels’s lifeless corpse pops up again and again whenever someone publishes an article about lynching in America. It graces the front cover of the landmark 2000 book, Without Sanctuary: Lynching Photography In America. It is also prominently displayed at the Equal Justice Institute’s museum in Montgomery, Alabama.

The County Commission denied the request to memorialize two of the most important events ever to take place on that Courthouse lawn. So later that year, a small crowed gathered to dedicate a historical marker provided by the Equal Justice Institute. Delbert Jackson, who fought to have the lynching memorialized on the Courthouse Square hoped that it’s current spot isn’t the marker’s final home. “It set me back a bit when county officials didn’t want to acknowledge it was a racial terror killing,” Jackson said at the dedication.

Shelby County Historical Commission Member Vanessa Davis, who opposed the Commission’s decision, also spoke at the ceremony. We see a legacy of slavery and terror lynchings, whereas you would think in 2018, you would see a legacy of the greatness that African-Americans have presented to this nation,” she said. “Because of the slavery and because of the terror lynchings, what we see is a terrorized, traumatized nation.”

When Chris and I visited Center, we went straight to the Courthouse Square to visit the site of the two lynchings. When we arrived, I already I knew the commemorative marker wasn’t on the courthouse square. But I wanted to see the spot where it happened. And there it was: courthouse annex’s familiar facade I saw on the postcard, facing out across a peaceful lawn and the bloodied soil, but otherwise undisturbed by unpleasant reminders.

It really is a very small town. I figured it wouldn’t be too hard to find the marker. I asked around to a few folks on the square. Where is it? No one knew. Said one lady, “It happened right over there. That’s not the same tree, but that’s where it happened. That’s where the marker should be, but it’s not there.” She tried to help. She suggested I ask at the county history museum around the corner and behind the First Baptist Church, but it was closed.

So Chris and I left, and pressed on to our next stop in Louisiana.

Later that night, from the comfort of our hotel room, I used Google Street View and compared it to news photos from the marker’s dedication ceremony and figured out where it is. It’s in Center, barely, on the corner of Hicks/Daniel’s Street and Martin Luther King Drive. It’s about a mile from the Courthouse and tucked far out of the way where it won’t bother anyone. If you want to see it, you’re going to have to work extra hard to find it. Shelby County wants it that way.

![[Emphasis Mine]](http://jimburroway.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/Leyendecker.jpg)