Dig deeper. Wherever you find the impulse to regulate sexual behavior, you’re probably going to find busybodies policing other kinds of human activity they don’t like. That busy intersection is well illustrated by something that came to light on May 3, 1967 on the campus of Wayne State University of Detroit.

Wayne State was (and is) an urban Detroit university, located just a couple of miles north of downtown. Unlike the famously active campus of the University of Michigan in nearby Ann Arbor, WSU’s 30,000-some were much quieter and less politically active. A lot of this had to do with the the fact that almost all of the students were commuters, with most of them at living home with their families. Once classes ended for the day, the campus was mostly deserted. With so few participating in dorm room rap sessions and nearly non-existent campus-based social activities, student “life,” such as it was, was minimal. Student apathy was the norm.

But what Charles Larson found would jolt students out of their apathy. Larson was a nineteen-year-old junior and chairman of the Student-Faculty Council. He learned that WSU’s Public Safety Department — the campus police — was keeping extensive files on “homosexuals, narcotics addicts, psychotics, parolees and ‘politically active’ students.”

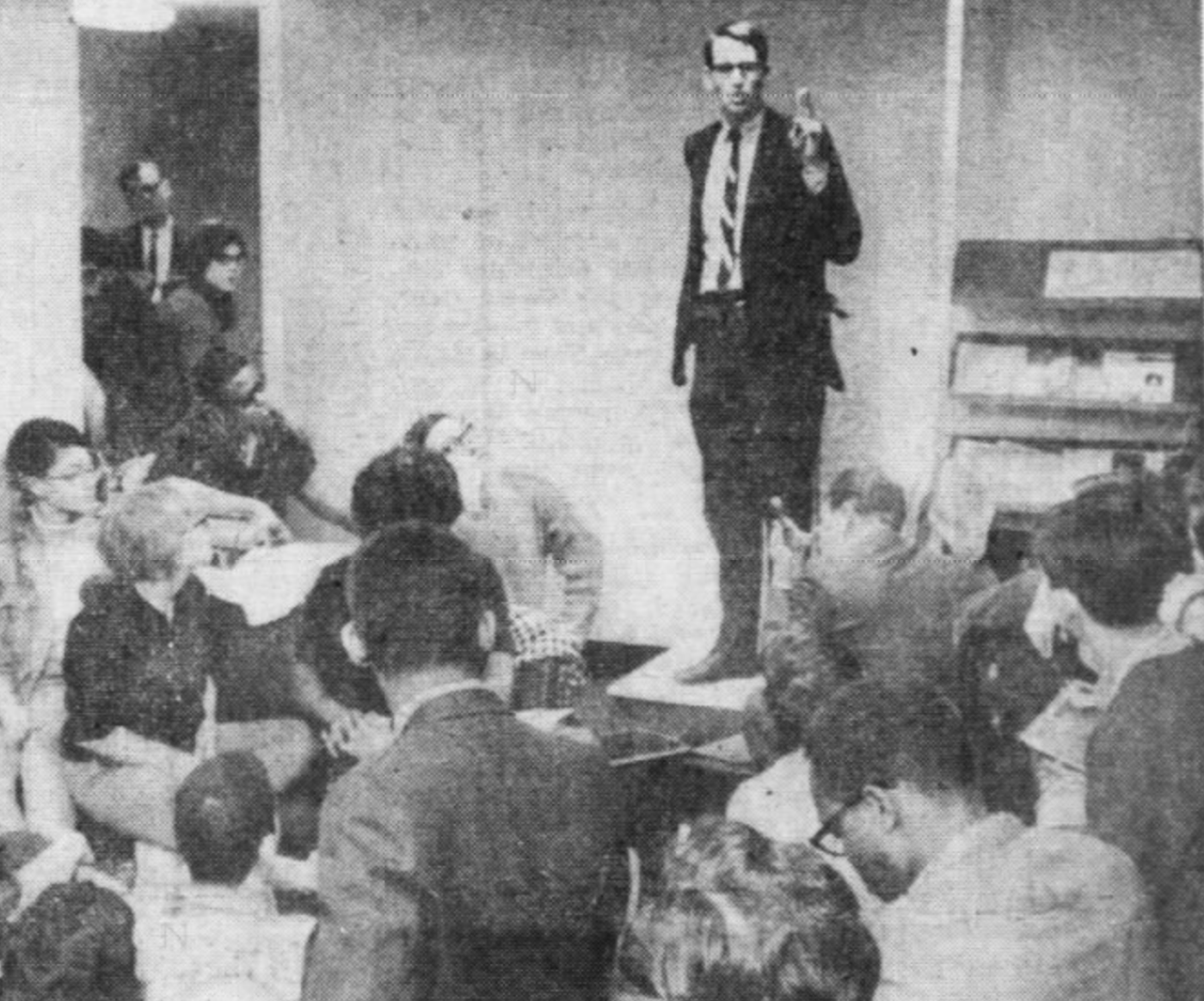

This sent shockwaves through the campus. Almost immediately, about fifty students began a 24-hour vigil outside of the offices of WSU president William Keast. They demanded the university hand over the files to a student committee, which would return the files to the individuals named in them.

But that was just a tiny fraction of what they wanted. After all, if WSU turned over the objectionable files, what was to prevent campus police from collecting a new set of files? To prevent that from happening, students demanded a substantial voice in how the university was run. Getting the files were just their first demand. They wanted academic issues turned over to students and faculty, a say in selecting school administrators, a voting student on all presidential advisory committees, student-faculty oversight over security procedures, binding referendums on student issues, and — this one was a particularly heavy lift — a change in the state’s constitution to put a student on the board of governors.

“The university exists for the students and the faculty,” said Larson. “The administration role should be to mow the grass and sweep the hallways, not to make decisions about my life.” The Detroit Free Press blasted the student’s “silly dispute over some outdated files”:

The silly season has begun at Wayne State University. The howling mob of students, protesters and representatives of the great unwashed might be taking themselves seriously, but it’s doubtful that the university’s administration can. What the students want is nothing short of taking over the school which, in case no one has told them, they are neither intelligence nor mature enough to do. … Granted we’re old-fashioned, but we’ve always been led to believe that university administrators administered and students studied. … If they don’t like it, they can go somewhere else, such as Vietnam.

But Larson was no stereotypical rabble rouser. Free Press reporter Barbara Stanton wrote, “Larson is indignant, not alienated. He will argue with Keast, but he will be wearing a tie and a clean shirt when he does it.”

At first, Vice President for Student Affairs James P. McCormick denied the files even existed. Larson promptly took McCormick to the campus police office and pointed at a file cabinet. McCormick pulled the drawer open, and there they were.

Some of the files dated back to the early 1950s. They included copies of police surveillance and arrest reports of gay students, along with other unofficial reports and notations added by campus police. Other files tracked students political activities, drug use surveillance and arrest records. One file labeled “psychotics” contained students’ private medical information. Another one, “demonstrators,” held newspaper clippings and photos of students at political protests, both on campus and off.

Campus President William Keast, who had only held the post for a year, denied knowing the files existed. Political dossiers, he said, would be “contrary to all I think a university should stand for” and should be destroyed. But the rest of the information, he said, was valuable to the university. Keast flat-out rejected any talk of turning over any of the files to a student committee. He cited — ironically, but appropriately — student privacy as the basis for his decision. Keast also rejected the students’ calls for an expanded role in the administration’s decision-making bodies and advisory committees. Echoing the Free Press, he said it would amount to a complete “takeover” by students.

By the afternoon of May 4th, a rally outside the administration building attracted about a thousand students. After the rally, about 350 went inside to join the sit-in. Others vowed to stay away from classes until their demands were met.

Later that evening, Keast met with Larson to diffuse the crisis. Keast proposed “a faculty-student-administration committee to review policy and procedures with respect to keeping records” — a first step. Then Keast and Larson, with two other students, watched as university employees carried files to the girls’ dormitory and burned them in the garbage incinerator.

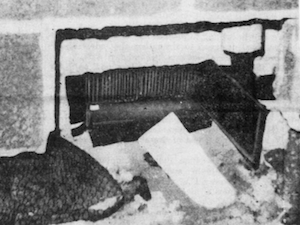

Things began to die down — for all of a week. On May 14, Larson learned that a hidden camera had been placed in a men’s room in State Hall. Larson said that three university employees, including a “minor administrator,” had tipped him to the camera’s location behind dummy grillwork. Larson photographed the hole in the wall of an adjacent room, where the camera had been placed facing into the grill to the men’s room. The camera itself was missing, although its imprint could still be seen on a piece of rubber foam left behind.

“You could see the face of everyone using the lavatory,” Larson said of the view through the grill. “I do not know if it has been used recently. But he (an employee) told me that it was in use a year to a year and a half ago.” One of the unnamed tipsters even signed an affidavit detailing the hidden camera procedure. The affidavit also revealed a wider spying effort on campus:

For four years (1962-1666) I have seen political meetings under surveillance and men’s rest rooms policed for moral offenses. The rest rooms were covered to apprehend known moral violators in action. A concealed camera was used in State Hall to catch offenders in their activities…

The political meetings were checked to see who attended, the number of students, the organization and the literature. A count of the crowd was made and the literature was filed.”

A WSU spokesman said that the secret films were taken about three years ago under former WSU President Clarence Hilberry. “I want to stress that this doesn’t mean something wrong was done,” said the spokesman. “We feel we have an obligation to the parents and the students to ensure that no one engages in illegal activity on campus.” He also added that “to the best of my knowledge,” the filming had been discontinued.

But Larson countered, “We feel that observing people in lavatories involves so many innocent people that this technique should not be used for breaking up such activities… We also object because the students did not know this was taking place.”

Larson pressed again for sweeping changes in how the university was run: “You talk to them, you listen, you try to make them understand and you think you’ve gotten somewhere, then you find out they’ve been lying to you. All we want is a say in deciding our own destiny.”

The university acquiesced, minimally. Keast announced that some of the administration’s advisory committees would now include student representatives. This time, even the Detroit Free Press was impressed:

The lesson to be learned at Wayne State University works two ways. The principal responsibility of a university student is to study but, just as important, the principal duty of an administration is to administer.

Administration has nothing to do with the outrageous fact that WSU security types concealed a camera behind a dummy ventilator in a men’s toilet.

Administration has nothing to do with tax-paid university sleuths secreting away files on such self-labeled students as “psychos” and “demonstrators.”

Administration has nothing to do with sending university “spies” to report on the meetings of leftwing or rightwing students groups.

Epilogue:

The brief campus flare-up was all but forgotten after the quarter ended. Then, two months later, the Detroit Riot — many call it the Detroit Uprising — topped the “Long Hot Summer of 1967” that saw race-based rioting in hundreds of cities across the country. The Detroit conflagration killed 43 and brought decades of police brutality and city indifference to the African-American community to the fore. It also began a radical transformation for both the city and the university. The city is only now recovering from the white flight, economic decline, and decades of mismanagement that followed.

The brief campus flare-up was all but forgotten after the quarter ended. Then, two months later, the Detroit Riot — many call it the Detroit Uprising — topped the “Long Hot Summer of 1967” that saw race-based rioting in hundreds of cities across the country. The Detroit conflagration killed 43 and brought decades of police brutality and city indifference to the African-American community to the fore. It also began a radical transformation for both the city and the university. The city is only now recovering from the white flight, economic decline, and decades of mismanagement that followed.

WSU saw major changes, too. The nearly all-white campus saw increasing numbers of African-American students over the next few years. And with it came a long, contentious struggle among students to come to terms with its newfound diversity in culture and political fervor. Larson’s tie and white shirt was out. The student newspaper, The Daily Collegian, became The South End in the fall of 1967, and embraced revolutionary Marxism and Black Power. Today, WSU and Detroit are enjoying a renaissance. The university is Michigan’s third-largest university and ranked in the top fifty public university for research expenditures.

WSU saw major changes, too. The nearly all-white campus saw increasing numbers of African-American students over the next few years. And with it came a long, contentious struggle among students to come to terms with its newfound diversity in culture and political fervor. Larson’s tie and white shirt was out. The student newspaper, The Daily Collegian, became The South End in the fall of 1967, and embraced revolutionary Marxism and Black Power. Today, WSU and Detroit are enjoying a renaissance. The university is Michigan’s third-largest university and ranked in the top fifty public university for research expenditures.

Also On May 3, 1967:

The New York Times reveals that Columbia University has chartered the country’s gay student group.

Periscope:

Headlines for May 3, 1967: Detroit African-American leaders fear a “tough summer” of racial relations. Dartmouth college students mob a car carrying Alabama Gov. George Wallace, who was there for a speaking engagement. Gen. William C. Westmoreland asks for 160,000 more American troops in South Vietnam, which would bring the total to well more than 600,000. President Lyndon Johnson denies a further buildup in Vietnam is imminent. Martin Luther King., Jr., urges “massive pressure” to desegregate housing in Louisville, Kentucky; Churchill Downs rejects Klan offer to preserve order on Derby Day. Prime Minister Harold Wilson’s government applies for British membership in the European Economic Community.

On the Radio: “Somethin’ Stupid” by Nancy and Frank Sinatra, “The Happening” by the Supremes, “Sweet Soul Music” by Arthur Conley, “A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You” by the Monkees, “Happy Together” by the Turtles, “I Think We’re Alone Now” by Tommy James and the Shondells, “Don’t You Care” by the Buckinghams, “You Got What It Takes” by the Dave Clark Five, “I’m A Man” by the Spencer Davis Group, “Jimmy Mack” by Martha and the Vandellas, “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” by Aretha Franklin.

On the Radio: “Somethin’ Stupid” by Nancy and Frank Sinatra, “The Happening” by the Supremes, “Sweet Soul Music” by Arthur Conley, “A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You” by the Monkees, “Happy Together” by the Turtles, “I Think We’re Alone Now” by Tommy James and the Shondells, “Don’t You Care” by the Buckinghams, “You Got What It Takes” by the Dave Clark Five, “I’m A Man” by the Spencer Davis Group, “Jimmy Mack” by Martha and the Vandellas, “I Never Loved a Man (The Way I Love You)” by Aretha Franklin.

On television: Bonanza (NBC), The Red Skelton Hour (CBS), The Andy Griffith Show (CBS), The Lucy Show (CBS), The Jackie Gleason Show (CBS), Green Acres (CBS), Beverly Hillbillies (CBS), Daktari (CBS), Bewitched (ABC), The Virginian (NBC), Gomer Pyle, USMC (CBS), The Fugitive (ABC), Get Smart (NBC), Star Trek (NBC), My Three Sons (CBS), Family Affair (CBS), Gilligan’s Island (CBS).

New York Times best sellers: Fiction: The Arrangement by Elia Kazan, The Eighth Day, by Thornton Wilder. Non-fiction: The Death of a President, by William Manchester, Madame Sarah: Sarah Bernhardt by Cornelia Otis Skinner,

Sources:

“WSU Chief Is Picketed.” Detroit Free Press (May 4, 1967): 3A.

Jerome Hanson. “WSU’s Protesters Launch Another All-Night Sit-In.” Detroit Free Press (May 5, 1967): 1A, 16A

“WSU Gets a Rebel ‘Ultimatum.” Detroit Free Press (May 6, 1967):” 3A

Barbara Stanton. “WSU Rebel Leader’s Motto: ‘Pressure Gets Things Done’.” Detroit Free Press (May 6, 1967): 3A.

Editorial: “Silly Season at WSU.” Detroit Free Press (May 6, 1967): 6A.

Stan Putnam. “Wayne State Men’s Room Filmed by Hidden Camera — Not Used in 3 Years, School Aide Says.” Detroit Free Press (May 15, 1967): 3A.

“WSU Accused of a Spy Plot.” Detroit Free Press (May 16, 1967): 3A

Barbara Stanton. “Should a University Police Its Students?” Detroit Free Press (May 16, 1967): 3A, 10A.

Editorial: “Wayne Pain.” Detroit Free Press (May 16, 1967): 6A.

Mike Thoryn and Jeff Hadden. “Report from WSU.” Michigan Daily (University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, May 18, 1967): 4.

![[Emphasis Mine]](http://jimburroway.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/McCarthyCohn.jpg)