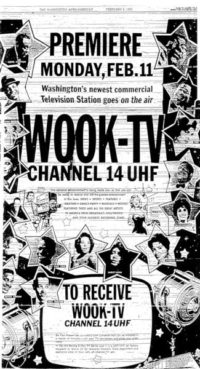

Washington, D.C’s WOOK-TV struggled to find an audience ever since it went on the air in 1963. Not that they didn’t try. The station looked at its local audience — 57% African-Americans, with many more across the line in Prince George’s County, Maryland — and decided to become the first American station to serve African-Americans. Its locally-produced programming included an American Bandstand-style program Teenarama Dance Party, a music program hosted by jazz great Lionel Hampton, and roving broadcasts from the city’s jazz nightclubs.

Washington, D.C’s WOOK-TV struggled to find an audience ever since it went on the air in 1963. Not that they didn’t try. The station looked at its local audience — 57% African-Americans, with many more across the line in Prince George’s County, Maryland — and decided to become the first American station to serve African-Americans. Its locally-produced programming included an American Bandstand-style program Teenarama Dance Party, a music program hosted by jazz great Lionel Hampton, and roving broadcasts from the city’s jazz nightclubs.

But as a UHF station, Channel 14 was hampered by a weak signal and the lack of TVs in the D.C. area capable of tuning in. Television sets weren’t required to be equipped with UHF tuners until 1964. Fewer blacks than whites owned TVs, and fewer people still paid extra to buy TVs with built-in UHF tuners. So it didn’t take long until low ratings and a lack of available programming forced WOOK to rely on cheap re-runs and thirty-year-old forgotten movies to fill out its schedule.

In 1967, WOOK decided to try something different by adopting a news/current affairs format for its evening schedule. Two and a half hours of news began at 7:30 p.m., followed by Controversy, a telephone call-in talk show moderated by Dennis Richards.

WOOK was apparently looking for controversial topics for Controversy. They found it when they invited local gay rights activists Frank Kameny and Jack Nichols, co-founders of the Mattachine Society of Washington (MSW), to appear on the February 7 program. This would make them among the very first guests to appear on Controversy.

As Nichols remembered it, it was a very cold and snowy night when they arrived at the WOOK studio. Nichols described Richards as “a mild-looking man.” But as soon as the on-the-air light lit up, Richards became “the most flamboyant and fierce adversary that has ever graced the television screen.”

Richards raised all of the classic fallacies: all gay men are drag queens, gay people are mentally ill, all homosexuals molest children — that sort of thing. Nichols later wrote that Kameny, “in his clear, logical and authoritative manner, squelched a great number of our adversary’s arguments.” Richards finally went ballistic:

Not only did he pound his fist on the desk, wave his arms about, interrupt, shout, and burst forth with diatribes of antihomosexual frenzy, but, as the show came to an exhausting end after two hours and while we were still on the air, he screamed, “Get off of my stage, out of my studio, you vicious perverted, lecherous people!!”

With time left to fill, Richards continued taking calls from his television audience. Many of those callers accused him of being overly-excited and said that he needed to calm down. Some even openly questioned if maybe he, too, was gay.

Ordinarily, one might look at what happened and conclude the whole thing was a disaster. But those phone calls suggested to Nichols that Richards’s antics actually helped them:

… Mr. Richard’s (sic) antics throughout the session on TV was pure melodrama, and since we had been able, in spite of his opposing spirit, to answer every question cooly and make our points effectively, he succeeded only in making himself look rather ridiculous and certainly unreasonable with respect to his antihomosexuality.

So imagine their shock when Kameny answered the phone one day and found someone from WOOK on the other end, asking if he and Nichols would like to come back for another round of Controversy. Kameny was never one to pass up a chance to engage the media, so he accepted immediately. Nichols also agreed. But this time, they brought along Lilli Vincenz (using the pseudonym of Lily Hansen), one of the few lesbians to join MSW.

This broadcast, on March 2, contrasted the previous one like night against day. Maybe the station’s management told Richards to calm down. Or maybe it was Vincenz’s presence — with her simple skirt, heels, a nice trim haircut and a shy smile. She might have been a lesbian, but with her appearance that night, nobody was going to try to call her a pervert. And also, maybe it’s because Vincenz sat between the two men, breaking up the possibility of the viewing audience (or Richards) imagining Kameny and Nichols together.

Whatever it was, Richards was a gentleman. “The second time he was as sweet as can be,” remembered Vincenz. “I don’t know if I made a difference, or if he had a change of heart and realized that wasn’t the way to deal with gay people.” Nichols agreed:

Mr. Richards had become tame. He didn’t shout, and he allowed us ample opportunity to have our say. Although he made it clear that he disagreed with our stand, he did not, as previously, throw his pencil on the floor, hurl insulting invectives at us, or say “You make me want to vomit!” Perhaps it had become clear to him, in retrospect, that he had not handled us in a manner which could be called “suave.” Also, perhaps the presence of a young lady made it less easy for him to wax nasty.

When the show came to an end, Richards thanked his guests for coming on. But he never offered an apology, on camera or off.

Kameny, Vincenz and Nichols considered this second program as successful as the first. This time, they were able to answer viewers’ questions much more calmly and without interruption. “The public didn’t know that the stereotype wasn’t true of the majority of gay people,” Vincenz said later. “Once we started appearing on TV and on talk radio shows, they started seeing us as more real. A lot of people connected because of our visibility.”

Epilogue:

Before Dennis Richards arrived at WOOK-TV, he had briefly hosted a two-hour afternoon radio call-in show for WACE in Springfield, Massachusetts. Broadcasting, a trade magazine, said the program consisted of “phone discussions on controversial subjects.” He didn’t last very long at WOOK. He was replaced in April.

Kameny and Nichols appeared on a CBS Reports documentary, “The Homosexuals” on March 7, just five days after their second WOOK appearance.

Then on March 22, Nichols drove up the road to Baltimore to appear on WJZ’s 45-minute talk show Contact, hosted by John Sterling. Appearing with Nichols was Rev. LeRoy Graham, chaplain at American University, Methodist bishop, and gay rights supporter. When CBS aired “The Homosexuals” two weeks earlier, the Baltimore affiliate WMAR refused to show it. WJZ took advantage of the controversy by heavily promoting this edition of Contact, using a photo of Nichols and a tagline, “The Second Largest Minority.” Nichols noted later, “The significance of this show lies in the fact that for the first time, a distinguished Methodist clergyman on the East Coast has publicly associated himself with the civil libertarian aims of the homophile movement and has made hls views known to a wide television audience.”

Periscope:

Headlines for February, 7, 1967: Blizzard strikes east coast; Washington, Baltimore buried under a foot of snow. U.S. forces finish a massive defoliation offensive in Vietnam using Agent Orange ahead of a four-day truce for Tet, the lunar new year and Vietnam’s most important holiday. Pentagon announces 1,172 total fixed-wing aircraft losses in Vietnam, and over 600 helicopter losses since the war started. Sino-Russian ties are near the breaking point as protesters in Moscow try to overrun the Chinese embassy; Moscow protesters are angered over Chinese violence against Soviet embassy in Peking. A fire sweeps through the posh Dale’s Penthouse restaurant on top of the Walter Bragg Smith building in Montgomery, Alabama; twenty-six are killed.

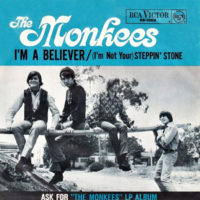

On the radio: “I’m a Believer” by the Monkees, “Georgy Girl” by the Seekers, “Kind of a Drag” by the Buckinghams, “Ruby Tuesday” by the Rolling Stones, “(We Ain’t Got) Nothin’ Yet” by the Blue Magoos, “Tell It Like It Is” by Aaron Neville, “98.6” by Keith, “Snoopy vs the Red Barron” by the Royal Guardsmen, “Love Is Here and Now You’re Gone” by the Supremes, “The Beat Goes On” by Sonny and Cher, “Stand By Me” by Spyder Turner.

On the radio: “I’m a Believer” by the Monkees, “Georgy Girl” by the Seekers, “Kind of a Drag” by the Buckinghams, “Ruby Tuesday” by the Rolling Stones, “(We Ain’t Got) Nothin’ Yet” by the Blue Magoos, “Tell It Like It Is” by Aaron Neville, “98.6” by Keith, “Snoopy vs the Red Barron” by the Royal Guardsmen, “Love Is Here and Now You’re Gone” by the Supremes, “The Beat Goes On” by Sonny and Cher, “Stand By Me” by Spyder Turner.

On television: Bonanza (NBC), The Red Skelton Hour (CBS), The Andy Griffith Show (CBS), The Lucy Show (CBS), The Jackie Gleason Show (CBS), Green Acres (CBS), Beverly Hillbillies (CBS), Daktari (CBS), Bewitched (ABC), The Virginian (NBC), Gomer Pyle, USMC (CBS), The Fugitive (ABC), Get Smart (NBC), Star Trek (NBC), My Three Sons (CBS), Family Affair (CBS), Gilligan’s Island (CBS).

New York Times best sellers: Fiction: The Secret of Santa Vittoria by Robert Crichton, Capable of Honor by Allen Drury. Non-fiction: Everything but Money by Sam Levenson, Paper Lion: Confessions of a Last-String Quarterback by George Plimpton.

Sources:

Warren D. Adkins (pseudonym for Jack Nichols). “The Washington-Baltimore TV Circuit.” The Homosexual Citizen (May 1967): 6-10.

Edward Alwood “A Gift of Gab: How Independent Broadcasters Gave Gay Rights Pioneers a Chance To Be Heard.” In Kevin G. Barnhurst (ed.) Media Queered: Visibility and its Discontents (New York: Peter Lang Publishing, 2007) : 27-43.

“Here’s How the All-Talk Stations Do It.” Broadcasting (June 27, 1966): 82-100.

![[Emphasis Mine]](http://jimburroway.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/DragInTheOpen.jpg)