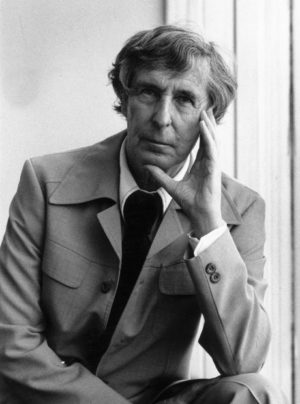

(January 2, 1905 – January 8, 1998) The British composer Michael Tippett has often been overshadowed by his contemporary, Benjamin Britten. Although both were conscientious objectors during World War II, Tippett was imprisoned for three months in 1943 as a conscientious objector while Britten avoided imprisonment.

(January 2, 1905 – January 8, 1998) The British composer Michael Tippett has often been overshadowed by his contemporary, Benjamin Britten. Although both were conscientious objectors during World War II, Tippett was imprisoned for three months in 1943 as a conscientious objector while Britten avoided imprisonment.

Tippett’s pacifism came to him by way of his first serious romantic relationship, with a young artist by the name of Wilfred Franks. They met in early 1932, when Tippett was still rather uncomfortable with his homosexuality. This relationship coincided with Tippett’s political maturation as a leftist and pacifist. Tippett will later write:

Meeting with Wilf was the deepest, most shattering experience of falling in love: and I am quite convinced that it was a major factor underlying the discovery of my own individual musical voice — something that couldn’t be analysed purely in technical terms: all that love flowed out in the slow movement of my First String Quartet, an unbroken span of lyrical music in which all four instruments sing ardently from start to finish.

Tippett dedicated his String Quartet No. 1, which premiered in 1935, to Franks. This quartet is regarded as the first in the recognized canon of Tippett’s compositions. Whether Tippett and Franks consummated their relationship is in dispute. Tippett’s letters suggest they may have, but Franks, who was even more uncomfortable with his sexuality than Tippett, always denied it. Tippett wrote:

Throughout this period, my relationship with Wilf was a tempestuous one. He was so sure that there was no such thing as being queer, though he certainly acted differently. We never talked about it fully. I simply kidded myself, as people often do, that if you desire someone strongly enough they will reciprocate……I clung to this feeling that Wilf would accept – but it would not work. He eventually found himself a girlfriend …

The acrimonious end of their relationship in 1938 threw Tippett into a deep emotional and sexual crisis. Never fully comfortable with his sexuality and harboring deeper self-doubts as an artist, Tippett turned to the Jungian psychotherapist John Layard. He emerged from that therapy with an appreciation for “the Jungian ‘shadow’ and ‘light’ in the single, individual psyche … the need for the individual to accept his divided nature and profit from its conflicting demands.” This provided new inspiration as an artist, and it allowed him to come to terms with his homosexuality. In 1941, he met the artist Karl Hawker, and they remained together until 1970.

Tippett’s politics often influenced his music. His wartime premiere of his pacifist oratorio, A Child of our Time, in 1944 (with Britten’s partner, Peter Pears, cast as soloist) received wide acclaim. The Times of London called it “strikingly original in conception and execution,” and The Observer hailed it as “the most moving and important work by an English composer for many years.”

The premieres of his First Symphony, Third Quartet, and Fantasia Concertante on a Theme of Corelli — one of his most popular and frequently performed works — soon followed. But audiences and performers alike found his 1955 opera The Midsummer Marriage confusing. Modeled after Mozart’s The Magic Flute, Tippett’s work recast it as a Jungian manifesto where, as he put it, “a warm and soft young man was being rebuffed by a cold and hard young woman to such a degree that the collective, magical archetypes take charge.” The music itself was well received, and he re-used the Four Ritual Dances from the opera as a separate concert work.

Controversy surrounded premieres of two following works: the Piano Concerto (1955, its first appointed soloist backed out after declaring it unplayable), and the Second Symphony (1957). During the Second Symphony’s premiere, the BBC Symphony orchestra actually broke during the live broadcast a few minutes into the first movement and had to be restarted.

Tippet visited America for the first time in 1955. That visit inspired him to incorporate jazz and blues into his music. His third opera, The Knot Garden, not only explored the complex themes of the Sexual Revolution, but also incorporated electric guitar and a drum set as part of the orchestra. His Third Symphony (1973) was influenced by American blues, with the solo soprano’s part being a tribute to the late blues singer Bessie Smith. But his fourth opera The Ice Break was roundly criticized for its hackneyed use of American slang and the inclusion of race riots and a psychedelic trip giving what The Telegraph calls “toe-curling results.” Nevertheless, Tippett’s popularity grew through the 1970s and 1980s. He died of a stroke in 1998, just six days after his ninety-third birthday.

Further Reading:

Michael Tippett. Those Twentieth Century Blues: An Autobiography (London: Hutchingson, 1991).

Michael Tippett. Tippett on Music (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1995).

Further Listening:

Piano Concerto/Fantasia On A Theme Of Handel/Fantasia Concertante On A Theme Of Corelli. Howard Shelly, piano. Bournemouth Symphony Orchestra; Richard Hickox (Chandos, 2001).

A Child of Our Time. City of Birmingham Symphony; Sir Michael Tippett (Naxos, 2005).

Symphonies No. 2 & 4. BBC Symphony Orchestra; Michael Tippet (NMC Recordings, 2005)

![[Emphasis Mine]](http://jimburroway.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/JuliusSipIn.jpg)