On November 27, 1949, the Palladium-Item of Richmond, Indiana, reported the following:

Prosecutor William H. Reller said he may invoke Indiana’s new Sex Crimes law in a sodomy case filed Saturday in Wayne Circuit court. John Catron, who said he lived at 40 Fort Wayne Avenue, is charged with sodomy in the affidavit filed by he prosecutor and Detective Sergeant John B. Murphy. Prosecutor Reller said he is investigating the case to determine whether the Sex Crimes law should be used.

Catron was arrested on a vagrancy charge Friday night after he admitted homosexual activities with two other men, police said. He was questioned after he came to police headquarters to make an inquiry, police reported.

Homosexuality was a very delicate topic, making it extremely difficult to figure out what was going on from sketchy newspaper reports like this. These articles tend to leave open far more questions than answers. First of all, what led Catron to go to the police station? What “inquiries” did he make? Was he a crime victim who wound up getting charged with a different crime? This wasn’t at all unusual. Many a gay man had found himself locked up after complaining that a sex partner stole something or beat him up.

Homosexuality was a very delicate topic, making it extremely difficult to figure out what was going on from sketchy newspaper reports like this. These articles tend to leave open far more questions than answers. First of all, what led Catron to go to the police station? What “inquiries” did he make? Was he a crime victim who wound up getting charged with a different crime? This wasn’t at all unusual. Many a gay man had found himself locked up after complaining that a sex partner stole something or beat him up.

And in this news report — and in all of those that follow — nowhere is there even a suggestion that Catron was having sex with minors. Newspapers of the day were not at all shy about trumpeting that sensational allegation in their pages. Nor is there any suggestion that there was any coercion, blackmail, use of force or threat of bodily harm. In fact, three days later, the Palladium-Item added this tidbit in another article:

Catron, Prosecutor Reller says, has admitted homosexual acts with two men with whom he lived.

Which, of course, brings up more questions: Who were these two men? Why weren’t they arrested? The Palladium-Item was strangely silent about all of that.

Indiana’s new Sex Crimes Law

In March of 1949, Indiana’s governor approved a brand new Sex Crimes law, and prosecutors across the state were itching to use it. The Indiana General Assembly enacted the statute while the state was gripped with a sex crime panic. The main impetus for the law sprang from the brutal rape and murder on November 13, 1947 of Mary Lois Burney, a prominent north Indianapolis suburban housewife, by Robert Watts, an African-American truck driver employed by the city. Watts, who had a criminal record stretching back to 1941, was out on a $250 bond (about $2,800 today) for an attempted rape, and yet he kept his job with the city. Watts was suspected of, but never tried for, perhaps a dozen other attacks, including the murder of Mabel Merrifield two weeks earlier.

The Watts arrest brought out all kinds of fears, not just of black men, but also that perverts were running loose in the city. He was eventually convicted and sentenced to die. The U.S. Supreme Court threw out that conviction because his confession came after a marathon six-day interrogation in which he was held without an arraignment and denied an attorney. He was tried and convicted again, and died in the electric chair in 1951.

Press reaction was only somewhat calmer when police arrested Ralph A. Williams, a mild-mannered (white) hearing-aid salesman who kidnapped and raped an eight-year-old girl. As the African-American weekly Indianapolis Recorder noticed, “So far as we have learned, there have been no community mass meetings on the question; householders have not taken to closing their doors on salesmen (any more than before); and nobody is driving around town and assaulting white pedestrians because of it.” But at least now everyone was on notice that nobody was safe and everyone was a potential suspect, no matter how ordinary or respectable they may appear to be.

Then in October, police arrested Orville Wiley, a married father of two and a former hospital orderly. He stood accused of molesting 42 children, some in hospitals, but most of them at thirteen grade schools in Hancock, Madison, and Marion counties, including four schools in east Indianapolis. He had been accused of similar crimes in 1943, but those charges were quickly forgotten after Wiley’s parents agreed to have him “submit to an operation.” There is no evidence that any kind of “operation” took place, and the case “just died, finally” without follow-up, according to the Hancock County prosecutor at the time. Judge Alex Clark spoke for many when he expressed his frustration at the maximum sentence he could give Wiley: six months in jail and a $500 fine (about $5,400 today). “There is nothing I can do about it,” complained the judge. “There must be some change in the laws and there is a definite need for some intermediate institution to take care of these cases.”

The General Assembly answered the call in 1949 with its new Sex Crimes Law. Modeled after similar sexual psychopath laws in Michigan and Illinois, it allowed for the indeterminate detention in a state mental institution of anyone deemed a “sexual psychopath.” Once committed, they would remain there “until such person shall have fully and permanently recovered from such criminal psychopathy.” To fall under this statute, a person need only be charged with a sexual crime (as long as it doesn’t involve “crime of murder or manslaughter, or rape on a female child under the age of twelve”) — he doesn’t need to be found guilty. Once charged, the defendant or the prosecutor can petition the court to proceed under the sexual psychopath statute. The court can then ask two physicians — neither of them are required to be psychiatrists — to examine the defendant. If both physicians agree that the defendant is a “sexual psychopath” (and what that means is not defined, either in the law or in psychiatry or medicine), the original charge is dropped and the defendant is locked away. For how long? Nobody can say.

The law, as written, invited abuse. A 1969 Indiana Law Review observed:

First, prosecutors can proceed against a defendant under the sexual psychopath statute even though they do not have sufficient evidence for a criminal conviction. This can occur either when there is a lack of evidence of guilt or when evidence of guilt is present, but inadmissible at a criminal trial. Second, prosecutors may threaten misdemeanor defendants with a sexual psychopathy proceeding in order to secure a guilty plea. While neither practice is illegal, both have a potential for abuse.

We will never know whether Richmond prosecutor William H. Reller had the evidence to convict John Catron because he immediately petitioned the court to invoke the sexual psychopath statute. The law wasn’t even a year old, but Reller already had some practice with it. In May 1949, Reller used it to send Enos Wicks to the state hospital in Michigan city. Wicks was accused — but not tried or convicted — of having committed sodomy. Again, the circumstances are obscure but, as with John Catron, the Palladium-Item never mentioned coercion or underage males as being a factor in Wicks’s arrest.

Catron’s case followed the same path as Wicks’s. Judge G.H. Hoelscher, the same judge who oversaw the Wicks case, named two local physicians, Drs. Louis F. Ross and Paul S. Johnson to examine Catron. (Johnson had also been called upon to examine Wicks.) Two weeks later, they came back with their verdict: Catron was, in their opinion, a “criminal psychopathic person.” After a break for the Christmas and New Years holidays, Catron was brought before Judge Hoelscher and committed to the state hospital for the criminally insane at Michigan City.

And all of that took place without the need to go through a bothersome and messy trial, with its due process and rules of evidence to get in the way.

Epilogue:

Under Indiana law, the penalty for sodomy was two to fourteen years’ imprisonment with a possible fine of $100 to $1,000 (about $1,110 to $11,100 today). In March 1952, when Catron would have been more than two years into a sentence for sodomy, he petitioned for a rehearing of his case. The same judge who sent him to Michigan city denied his petition. After that, the trail goes cold.

The case of John Catron, and Enos Wicks before him, is far from unusual. In 1957, the Indiana Law Review published a review of all of the sexual psychopath cases to date, and found sixty men were committed for sodomy. As many as thirty-two of them appear to have involved consensual relationships with adults. In the same period, only thirty-six men and three women were sent to the state prison or reformatory for sodomy.

On the Timeline:

![]() Jan 4, 1950: Indiana’s Sexual Psychopath law ensnares a gay man.

Jan 4, 1950: Indiana’s Sexual Psychopath law ensnares a gay man.

Periscope:

For January 4, 1950:

| President: | Harry S. Truman (D) | |||

| Vice-President: | Alben W. Barkley (D) | |||

| House: | 263 (D) | 167 (R) | 2 (Other) | 3 (Vacant) |

| Southern states: | 103 (D) | 2 (R) | ||

| Senate: | 54 (D) | 42 (R) | ||

| Southern states: | 22 (D) | |||

| GDP growth: | 7.3 % | (Annual) | ||

| 3.0 % | (Quarterly) | |||

| Fed discount rate: | 1½ % | |||

| Inflation: | -2.1 % | |||

| Unemployment: | 6.5 % | |||

Headlines: In President Truman’s State of the Union Address, he asks Congress to extend rent controls and other emergency measures to deal with the post-war housing shortage. The U.S. State Department, angry at Hungary’s treatment of American citizens, orders the closure of Hungary’s consulates in New York and Cleveland. Coal strike forces cancellation of one-third of railroad passenger service. The New York Sun publishes its last edition. Major flooding on the Ohio River and its tributaries close sixteen main highways in Indiana and isolate two towns.

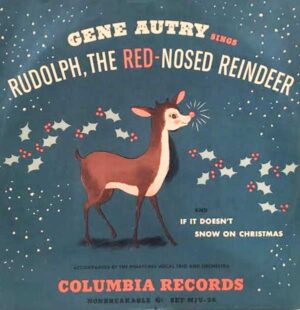

In the record stores: “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” by Gene Autry, “Mule Train” by Frankie Lane, “I Can Dream It, Can’t I?” by the Andrew Sisters, “Slipping Around” by Margaret Whiting and Jimmy Wakely, “I Yust Go Nuts at Christmas” by Yogi Yorgesson (Harry Stewart), “A Dreamer’s Holiday” by Perry Como, “White Christmas, ” Dear Hearts and Gentle People” and “Mule Train” by Bing Crosby, “Yingle Bells” by Yogi Yorgesson (Harry Stewart), “Blue Christmas” by Russ Morgan and his Orchestra.

In the record stores: “Rudolph the Red-Nosed Reindeer” by Gene Autry, “Mule Train” by Frankie Lane, “I Can Dream It, Can’t I?” by the Andrew Sisters, “Slipping Around” by Margaret Whiting and Jimmy Wakely, “I Yust Go Nuts at Christmas” by Yogi Yorgesson (Harry Stewart), “A Dreamer’s Holiday” by Perry Como, “White Christmas, ” Dear Hearts and Gentle People” and “Mule Train” by Bing Crosby, “Yingle Bells” by Yogi Yorgesson (Harry Stewart), “Blue Christmas” by Russ Morgan and his Orchestra.

On the radio: Lux Radio Theater (CBS), Jack Benny Program (CBS), Edgar Bergan & Charlie McCarthy (CBS), Amos & Andy (CBS), Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts (CBS), My Friend Irma (CBS), Walter Winchell’s Journal (ABC), Red Skelton Show (CBS), You Bet Your Life (NBC), Mr. Chameleon (CBS).

On television: The Lone Range (ABC), Toast of the Town/Ed Sullivan (CBS), Studio One (CBS), Captain Video and his Video Rangers (DuMont), Kraft Television Theater (NBC), The Goldbergs (CBS), Arthur Godfrey’s Talent Scouts (CBS), Candid Camera (NBC), Texaco Star Theater/Milton Berle (NBC), Hopalong Cassidy (NBC), Cavalcade of Stars/Jackie Gleason (DuMont), Meet the Press (NBC), Roller Derby (ABC).

New York Times best sellers: Fiction: The Egyptian by Mika Waltari, Mary by Sholem Asch, A Rage to Live by John O’Hara. Non-fiction: White Collar Zoo by Clare Barnes, Jr., This I Remember by Eleanor Roosevelt, Home Sweet Zoo by Clare Barnes, Jr.

Sources:

Newspapers and magazines (in chronological order):

Leo M. Litz. “Indignant citizens want answer to crime wave” Indianapolis News (November 13, 1947): 1.

Charles S. Preston. “Undue hysteria aroused by late crime outbreak.” Indianapolis Recorder (November 22, 1947): 1, 2. The Indianapolis Recorder was a prominent weekly newspaper serving Indiana’s African-American communities.

“Child rapist confesses. Police hold executive in assault.” Indianapolis Star (April 14, 1948): 1, 10.

Editorial: “What, no crime wave?” Indianapolis Recorder (October 24, 1948): 10. “Readers have called to our attention the comparative calm with which the daily press, radio and general public have taken the case of Ralph Aran Williams… We have even been urged to give the Williams case the ‘Watts treatment’ — that is, to describe the prisoner as a ‘burly white man,’ etc.”

“Hospital molester has record of abuse.” Indianapolis Star (October 12, 1942): 1.

“Confesses molesting 42. Fortville man bares misconduct.” Indianapolis News (October 19, 1948): 1, 18.

“Judge hits sex law weakness.” Indianapolis News (October 21, 1948): 1, 8.

“Sex criminal to be sent to state mental institution.” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN: May 25, 1949): 2.

“Watts: Court rules for fair hearing; new trial set for October 3.” Indianapolis Recorder (July 2, 1949): 1.

“May use new sex law in sodomy case.” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN: November 27, 1949): 1.

“To use sex crimes law in local case.” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN: November 29, 1949): 1.

“Two physicians to report in sodomy case.” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN: November 30, 1949): 1.

“Sex criminal report filed by 2 physicians.” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN: December 14, 1949): 1.

“Sex criminal will be sent to hospital.” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN: January 4, 1950): 2.

“Convicts’ peas for new hearings denied by judge.” Palladium-Item (Richmond, IN: March 3, 1952): 2.

journal articles:

Elias S. Cohen. “Administration of the Criminal Sexual Psychopath Statute in Indiana.” Indiana Law Review 32, no. 4 (Summer 1957): 450-466. Available online here.

Anthony Granucci, Sisan Jamart Granucci. “Indiana’s Sexual Psychopath Act in operation.” Indiana Law Review 44, no. 4 (Summer 1969): 555-594. Available online here.

![[Emphasis Mine]](http://jimburroway.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/JuliusSipIn.jpg)